[Updated Aug 31,2023]

This week the Lancet published an extended piece by Boston University’s Sandro Galea reflecting on a new bioethics book by Jonathan Marks, The Perils of Partnership: Industry Influence, Institutional Integrity, and Public Health.

Galea commences with a truism: “those of us who make a living in public health, be it in the academic world or in practice, have a near reflexive suspicion of working with the private sector. We come by that suspicion honestly. There is abundant research, evidence, and experience of how some industry practices have harmed the health of the public.”

And abundant research is almost an understatement. In medicine, the debate about the ethics of the cash register arises most often over drug company money. Here, the research evidence is clear: those who take pharmaceutical research money tend to not bite the hand that feeds them.

A 1998 New England Journal of Medicine study reported that 23 of 24 authors (96%) defending the safety of calcium channel antagonists had financial ties with manufacturers of these drugs. This compared with 11 of 30 (37%) who were critical of their use.

The University of Sydney’s Charles Perkins Centre Professor Lisa Bero is perhaps the world’s leading authority on competing interests in science and the way that engagement so often evokes the tale about those paying the (research) piper, calling the tune. Bero and others’ 2012 Cochrane Collaboration review investigated the association between pharmaceutical industry funding and research conclusions favourable to the companies funding the research.

Bero’s paper with Jenny White on corporate manipulation of research across five different industries (tobacco, pharmaceuticals, lead, vinyl chloride and silica) is another classic paper in the field.

Several research journals refuse to consider papers for publication which are authored by anyone with tobacco industry financial ties. Their reasoning? As the editors at PLoS put it in 2010:

“We remain concerned about the industry’s long-standing attempts to distort the science of and deflect attention away from the harmful effects of smoking.

That the tobacco industry has behaved disreputably – denying the harms of its products, campaigning against smoking bans, marketing to young people, and hiring public relations firms, consultants, and front groups to enhance the public credibility of their work – is well documented.

There is no reason to believe that these direct assaults on human health will not continue, and we do not wish to provide a forum for companies’ attempts to manipulate the science on tobacco’s harms.”

As PLoS journals charge authors a fee to publish, they also did not want to be accepting money obtained from the sale of tobacco and the millions of deaths involved in those sales.

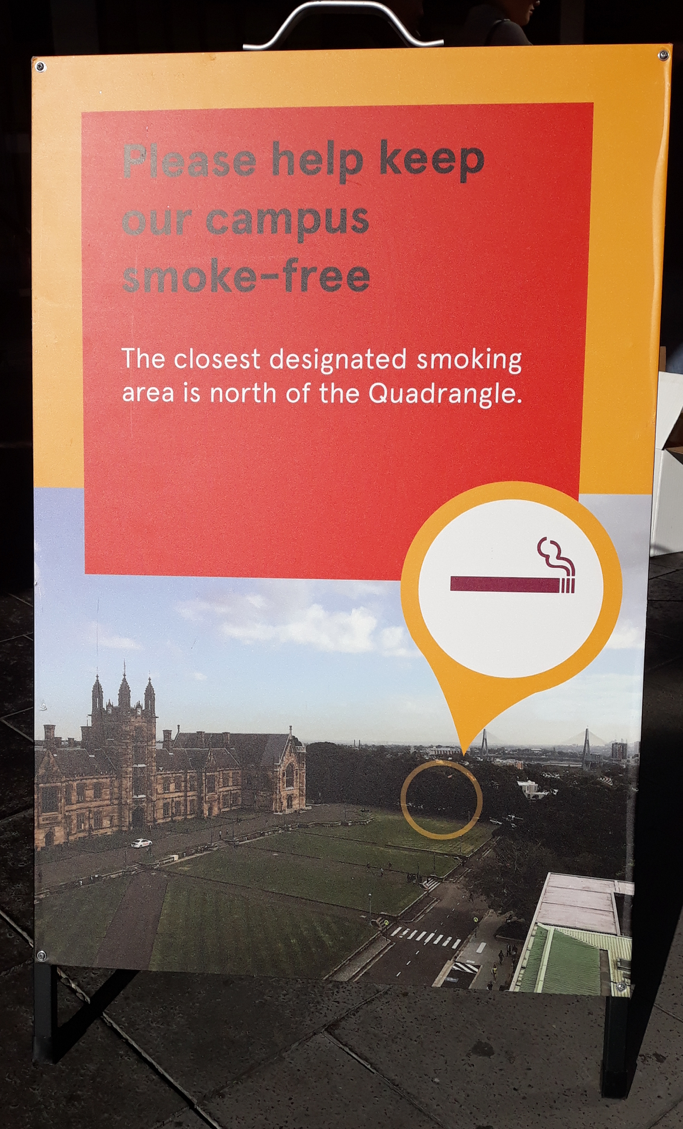

Tobacco-funded research and the conduct of the industry which oversees it has arguably the worst of all reputations. This explains why that industry is unique among all others in being barred from funding research and scholarships at many universities. My own institution – the University of Sydney – was one of the first to do this in 1982.

Bero’s contributions have been supplemented by Nicholas Freudeberg’s Lethal but legal (2014) and a book by the University of Auckland’s Centre for Addiction Research Peter Adams, Moral Jeopardy: Risks of accepting money from the Alcohol, tobacco and gambling industries (Cambridge University Press 2016).

Adams sets out with enormous erudition and many examples, the conduct of the three industries on which he focuses (alcohol, tobacco and gambling). He describes risks to reputations, governance, scientific neutrality, relationships and even to democracy when the corrupting influence of money from industries whose commercial well-being depends on successfully resisting any policies, laws and regulations that threaten their profitability inhibits those developments.

The main focus of his book is the ethical and moral questions which arise for health-care providers, researchers, universities, journals, and communities when such engagement occurs. The book has extensive sections elaborating on inventories of questions that all organisations contemplating accepting funding from these industries should ask themselves.

Manichaean simplicity?

All universities encourage their staff to engage with industry. But academics lamenting the decline of government funding for universities have often been scathing about this development and mocked industry-sponsored chairs. I recall one in “structural clay brickwork” was mercilessly pilloried. But why? What exactly is the ethical problem with assisting in advancing the quality of commercially made bricks? Or of improving steel through the University of Wollongong’s BHP funded chair?

Bricks and steel have innumerable uses which enhance human life and well-being. Life would be unarguably worse without them.

Sandro Galea’s Lancet piece notes that a central argument of Marks’ book is that

“Given that private-sector actors inevitably have their own commercial interests as one of their priorities, it is …impossible to maintain institutional integrity when one partners with actors whose mission is misaligned with one’s own.”

But Galea, who highly recommends the book, concludes by disagreeing with its main “disengagement” conclusion

“Simply put, I do not think it is possible, nor desirable, for public health to disengage from corporate sector partners; the public–private relationship is here to stay and we should be using Marks’s work to thoughtfully inform such engagements, not as a guide to disengagement”

My own view on industry engagement runs like this.

There are some industries which make and promote products or provide services where the net consequences of consumption are sometimes hugely negative. My personal list here includes fossil fuel industries, the nuclear power industry, tobacco, firearms, gambling, any industry with a track record of exploitative labour practices, irredeemable environmental pollution, or unsustainable pillaging of forests, land or oceans.

Then there is a huge middle group where simple Manichaean (good or evil) categorisations cannot easily withstand even basic scrutiny, and where significant negative and positive consequences of consumption cannot be ignored. Most people who drink alcohol do not harm others because of their drinking, but derive obvious pleasure from it. They may slightly increase their risk of dying from some diseases and shave some months or years off normal life expectancy, but prefer to take that chance. But alcohol causes massive harms across populations.

Here, Cambridge University’s Prof Sir David Spiegelhalter, a statistician, has eloquently written about the very small absolute risks of harm faced by those who drink alcohol moderately. He writes:

“Next look at 2 drinks a day, that’s 20g, or 2.5 units, slightly above the current UK guidelines of 14 units a week for both men and women.

In this case, compared to non-drinkers an extra 63 (977–914) in 100,000 people experience a health problem each year. That means, to experience one extra problem, 1,600 people need to drink 20g alcohol a day for a year, in which case we would expect 16 instead of 15 problems between them. That’s 7.3 kg a year each, equivalent to around 32 bottles of gin per person. So a total of 50,000 bottles of gin among these 1,600 people is associated with one extra health problem. Which still indicates a very low level of harm in drinkers drinking just more than the UK guidelines.”

I am of course not the only person grateful for the pharmaceutical industry as I reflect on drugs and vaccines I have taken to prevent or manage serious health problems, ameliorate pain or induce anaesthesia in surgery.

The cars, motorbikes, buses, trains and aircraft I’ve used, and electricity and gas have all used polluting fossil fuels. Many hope desperately for the rapid uptake of electric transport powered by renewable energy. Unlike the dilettante tobacco industry which refuses to stop making and promoting cigarettes while trying to spread nicotine addiction with ecigs and posturing about its responsible rebirthing, many major vehicle manufacturers are setting targets for complete transition away from petrol and diesel powered options.

My kitchen pantry is filled with grocery items that I select to consume, and not being heavily into hypocrisy, I don’t gag with ethical confusion when I eat them, despite some being produced by heinous transnational food companies . Instead, I am grateful that these companies are able to manufacture food items that I’m pleased to buy and eat. I can exercise my personal ant’s worth of consumer power by selecting product formulations and companies that tick all the important boxes. I can megaphone the availability of powerful apps like Cluckar (for boycotting misleading “free range” egg brands) and the George Institute’s Food Switch (which provides comparative ingredient information tens of thousands of grocery items) which help immensely with this.

So with all these examples, only the most doctrinaire or extreme will argue that these profit maximising industries are pure evil and have nothing to contribute to global health and well-being. Here, research engagement between the industries and university researchers is therefore common with constantly evolving effort to ensure research integrity is protected in areas like transparency and full declarations of competing interests. Researchers should engage with their fully-honed sceptical facilities on open display, as should always be the case in any research engagement.

When collaboration is urgent

Then there is a third category of industry where public health and industry are in all but total lockstep. Obvious examples here are renewable energy, vaccines, condoms, bicycles and with fruit and vegetable growers (and retailers).

When public health researchers working toward ways of reducing reliance on fossil fuels try to produce breakthroughs on renewable energy costs and efficiencies, they want their work to be commercialised so that it proliferates as fast as possible. That is the whole point of what they are working toward. The dire, accelerating existential threat posed by global warming makes the partnerships between the research and commercial sectors extremely urgent.

When communicable disease researchers produce new vaccines for self-evidently potentially catastrophic diseases like ebola, or partner with vaccine manufacturers in the common goal of maximising distribution, cold-chain standards and intelligence sharing, what’s not to like?

The pharmaceutical industry has more than once engaged in despicable price maximisation at times of communicable disease crises. It is reasonable to fear that specialist researchers affiliated in good faith in partnerships with such companies might self-censor concerns to condemn such practices, not wanting to bite the hand that has been feeding them. But to move from evidence of such conduct to a conclusion that there should be no collaboration in common, important purpose seems disproportionate.

When the world urgently needs to see significant uptake in use of commercially manufactured products, a chorus of criticism that inhibits the sharing of effort between researchers, these industries and government can be very myopic.