[updated 27 March, 2020]

Since I published this blog this time last year, I’ve seen a further critique written by Prof Matthew Peters, a respiratory specialist from Sydney’s Concord Hospital and former chair of Action on Smoking and Health Australia. Here it is, with the original blog following below)

Electronic cigarettes vs NRT for smoking cessation – the sting is in the tale.

In February 2019, Hajek and others published results of a randomised trial of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT n=446) vs use of a second-generation refillable e-cigarette device (n=438) in the New England Journal of Medicine. Subjects were all self-selecting attenders at U.K. National Health Service stop-smoking services.

The paper attracted considerable attention as it was a randomised study with an active control arm and used modern e-cigarette (EC) devices. Compared to the few previous randomised trials which used earlier generation ECs, it had a substantially greater effect size with relative risk of 1.75-1.84, (depending on adjustments and exclusion of certain subjects) for the primary outcome variable of continuous abstinence at 52 weeks. In media discussions since, this effect was commonly rounded up to a doubling of smoking cessation compared to NRT.

Three other smoking cessation outcomes were also reported or calculable from data in the paper and the associated supplement.

- Intention to treat (ITT) allocation to EC was not associated with reduced risk of relapse beyond 4 weeks after the target quit date. This was so even though EC use continued at a rate of 40% vs 4% for NRT.

- The relative risk (RR) for 7 days point-prevalence abstinence at 52 weeks was 1.52 for EC vs NRT

- The RR for continuous abstinence and being smoke and nicotine free at 52 weeks was approximately 0.5 for EC vs NRT. The ITT e-cigarette arm had 14 (3.1% smoke-free/nicotine free subjects compared to 31(6.9%) in the NRT arm.

If the beneficial effect is based on factors within the first 4 weeks, it is critical to exclude biases in the administration of the intervention and control treatments and to consider whether there may have been participant biases. Here, it is a problem that the control intervention was poorly applied. In the first 4 weeks, only 10% reported use of NRT daily vs 53% for those randomised to e-cigarettes. 25% of the NRT subjects used it on 19 or fewer days.

The investigators sought per protocol to exclude potential participants who may not have been equally disposed to one or other treatment but probably did not succeed. 91 NRT subjects did not complete 4-week follow-up compared with only 63 with e-cigarettes and these were counted as continuing or relapsed smokers as is standard practice in trials. Reinforcing the probability that the participating subjects were more favourably disposed to EC than NRT, crossover from NRT to e-cigarettes occurred around three times more often than e-cigarettes to NRT. In contrast, there was no difference for varenicline.

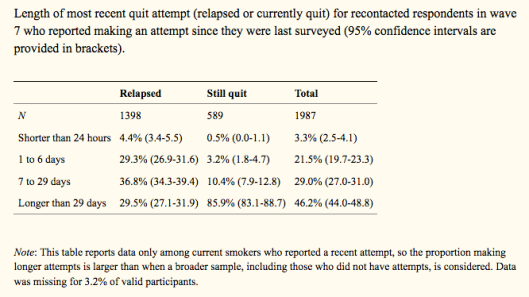

Critically, a statistical oddity underpins the high relative risk for continuous abstinence at 52 weeks. Continuous (CA) or prolonged abstinence and CO-confirmed 7-day point prevalence abstinence (PPA) are equally valid, highly correlated smoking cessation study end-points. CA cannot, by definition, exceed PPA. Hughes and others found a ratio of 0.74 from a systematic review of smoking cessation intervention studies. Viewing consolidated data from the paper and supplement in one table provides the best insight into the problem.

| PPA- EC (n) | CA-EC(n) | CA/PPA Ratio | PPA-NRT(n) | CA-NRT(n) | CA/PPA Ratio | RR for PPA

(unadjusted) |

RR for CA

(unadjusted) |

|

| 4 weeks | 195 | 192 | .985 | 136 | 134 | .985 | 1.46 | 1.45 |

| 26 weeks | 158 | 155 | .981 | 115 | 112 | .974 | 1.39 | 1.40 |

| 52 weeks | 146 | 79 | .541 | 98 | 44 | .449 | 1.52 | 1.83

(Primary comparison) |

Abbreviations used: CA continuous abstinence; PPA point prevalence abstinence; RR relative risk

What is clear that a dramatic fall at 52 weeks in CA/PPA for e-cigarettes and an even greater fall for NRT were required to achieve the headline relative risk for continuous abstinence with both ratios being well outside Hughes’ mean estimate. It is possible that the standard for continuous abstinence (not more than 5 cigarettes after quit date) contributed to CA/PPA being so different at 52 weeks compared to 26 weeks but this does not explain why the decline for NRT was so much greater.

Until this anomaly is explained, we are left with the more solid smoking cessation data being 7-day point prevalence CO-confirmed abstinence. That figure of about 1.5 at 52 weeks could still suggest that high nicotine delivery systems outperform older generation e-cigarettes for cessation outcomes but this finding would still need to be considered in the light of sharp differences in the application of e-cigarettes and NRT control in the critical first 4 weeks.

Behavioural support

Importantly, all trial participants also received “weekly behavioural support for at least 4 weeks”, with the authors noting in their conclusion that “E-cigarettes were more effective for smoking cessation than nicotine-replacement therapy, when both products were accompanied by behavioral support.”. This support “involved weekly one-on-one sessions with local clinicians, who also monitored expired carbon monoxide levels for at least 4 weeks after the quit date.” Eighty one percent of participants received 4 or 5 support sessions.

However, in real world use of either NRT or ecigs for smoking cessation, only a very small proportion of smokers would receive such support. Important questions therefore arise about the relative contributions of NRT and ecigs, to that of the support which all received. A study of a national English prospective cohort of 1560 smokers found “the adjusted odds of remaining abstinent up to the time of the 6-month follow-up survey were 2.58 (95% CI, 1.48-4.52) times higher in users of prescription medication in combination with specialist behavioral support”. However “The use of NRT bought over the counter was associated with a lower odds of abstinence (odds ratio, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.49-0.94).” This suggests that real world use of NRT without support may be ineffective.

Serious adverse events

The notion that new-generation e-cigarettes would be able to deliver more of the “good stuff”, nicotine, and not more of the bad stuff – toxic products of superheated vehicle solvents and flavourants was always questionable. This study reports numerically more serious adverse events in the e-cigarette arm than the NRT arm – 27 vs 22. Excluding malignancies, there were 7 potentially smoking related serious adverse events (SAEs) – one fatal- in the e-cigarette arm and 4 in the NRT group even though smoking rates remained higher in the NRT arm. Of the 5 respiratory events with e-cigarettes (vs 1 with NRT), the investigator concluded in each case that e-cigarette use was unrelated. The risk disparity 1.1% vs 0.2% was in the authors’ published conclusion – “likely a chance event”. This would suggest that there is a lack of objectivity and/or openness to emerging risks of e-cigarettes.

These safety findings are consistent with the failure of e-cigarette use, whether as complete or partial substitution for smoking, to reduce potential smoking-related disease or to meaningfully improve general health in a 4-year prospective study. Here with no reduction in potentially smoking related serious adverse events and an imbalance in respiratory SAE’s, serious doubts are created in relation to claims that use of latest generation e-cigarettes is 95% safer than smoking; if it is safer at all.

********************************************************************************

Original blog

The New England Journal of Medicine has just published the results of a randomised controlled trial on the relative efficacy of e-cigarettes v nicotine replacement therapy.

Here are the results and conclusions from the abstract (the full article is paywalled).

Results A total of 886 participants underwent randomization. The 1-year abstinence rate was 18.0% in the e-cigarette group, as compared with 9.9% in the nicotine-replacement group (relative risk, 1.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.30 to 2.58; P<0.001). Among participants with 1-year abstinence, those in the e-cigarette group were more likely than those in the nicotine-replacement group to use their assigned product at 52 weeks (80% [63 of 79 participants] vs. 9% [4 of 44 participants]). Overall, throat or mouth irritation was reported more frequently in the e-cigarette group (65.3%, vs. 51.2% in the nicotine-replacement group) and nausea more frequently in the nicotine-replacement group (37.9%, vs. 31.3% in the e-cigarette group). The e-cigarette group reported greater declines in the incidence of cough and phlegm production from baseline to 52 weeks than did the nicotine-replacement group (relative risk for cough, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.6 to 0.9; relative risk for phlegm, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.6 to 0.9). There were no significant between-group differences in the incidence of wheezing or shortness of breath.

Conclusions E-cigarettes were more effective for smoking cessation than nicotine-replacement therapy, when both products were accompanied by behavioral support.

This study is already causing the predicted outbreak of gushing hyperbole from e-cigarette interests and their urgers.

Professor Martin McKee, from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, has shared the following comments about the paper that are very useful.

“The subjects were people who had already decided to attend a stop smoking service. Then, randomisation only began after they had set a quit date. In other words, they were very far from a random sample of smokers. They also excluded existing dual users. [note dual e-cig and cigarette use is by far the most common way that e-cigarettes are used].

Outcome was self-reported use of less than 5 cigarettes from 2 weeks post enrollment to 1 year, and validated, but only by 1 biochemical (CO) test at 1 year, which would only capture very recent smoking.

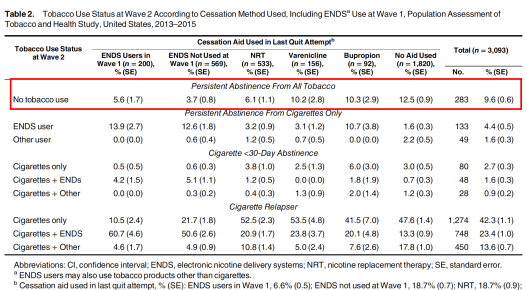

Among those who did give up, 80% in the e-cig group were still using them, but only 9% of the NRT group were using NRT. Given evidence from other studies, such as the US PATH study, that over longer periods quite a lot of e-cig users relapse, it will be important to look at longer term follow up. (The authors say 80% is “fairly high”!)

They say “Provided that ongoing e-cigarette use has similar effects to long-term NRT…” but then refer to 1988 study. And they say nothing about health risks of e-cigs.

Finally, as they note, this study is inconsistent with 3 previous ones.

So, in summary, I would say:

“This study differs from previous ones in finding that e-cigarettes do seem to be better than NRT at maintaining abstinence, at least for one year, in a highly selected group of people who have already decided to quit and have taken steps to get help with it. Of course, the vast majority of those who quit do so unaided, but, nonetheless, these findings are interesting, although it will be important to see what happens in the longer term. It is, however, important to recognise that it only relates to those who are using e-cigarettes when linked to face-to-face support from a smoking cessation service. It tells us nothing about their use in the wider population of smokers, which is where many of the concerns lie.”

Here’s another comment

“E-cigarettes may be better than the nicotine replacement alternative in the [NEJM] study — but they only helped a minority of participants in the vaping group quit. “In spite of the concerted effort and encouraging findings, it is still disappointing,” said David Liddell Ashley, the previous director of the office of science in the Center for Tobacco Products at FDA [Food & Drug Administration]… So this randomized controlled trial might — and probably should — encourage health professionals to consider e-cigarettes, at least the type shown to be effective in the study, as a tool for their smoking patients. But it also shows e-cigarettes are far from the panacea some suggest they might be.” [Julia Belluz. Study: Vaping helps smokers quit. Sort of. Vox]

Behavioural support: little real world relevance

To this I would emphasie that the participants in the trial received not only e-cigarettes or NRT, but they self-selected to attend a quit smoking service and received “behavioural support”. This means these subjects were very different to random e-cigarette or NRT users in the English community, the great majority of whom do not elect to attend such services.

In Australia, despite the quitline phone number being on every cigarette pack and it being hammered in many quit smoking campaign ads, only 3.6% of smokers ever called the quitline over a year. Far fewer are interested in attending “behavioural support” sessions. So this paper has very important limitations in its relevance for debates about whether e-cigarettes (or NRT) can assist people to quit under conditions of real world use.

We know from recent real world longitudinal studies of people who vape in the USA that e-cigarette users actually do worse with quitting than those who use other forms of smoking cessation aids, and particularly those who quit unaided. I covered this in an earlier blog here.

We also know that over-the-counter NRT, used without support in the normal way that nearly all users use it, is not effective. See for example here (“The use of NRT bought over the counter was associated with a lower odds of abstinence (odds ratio, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.49-0.94).). In other words, using NRT like this might actually prevent quitting. Big Tobacco, now with major investments in e-cigs and heat-not-burn products, will be praying the same thing is true for e-cigs. And if they are wise investors, also very confident that the net effect of e-cigarette proliferation will be to keep far more people in smoking than are tipped out of it, and that it will provide nicotine addiction training wheels to many children who have never smoked and probably never would have.

Source: Sydney Morning Herald

Source: Sydney Morning Herald