Updated 8 Aug 2023 (see end of blog)

Image by Brian Neises from Pixabay

The Australian government announced in May that it is now illegal to import or retail nicotine vaping products into Australia unless these products are destined for sale in pharmacies to those with a doctor’s prescription for a nicotine vaping product.

These products will be sealed “pod” systems where the liquid containing nicotine and flavouring chemicals and the battery that heats and vapourises the liquid will be sealed, with attempts to open it destroying the integrity of the product.

Many older vapers use vaping systems which allow the user to remove the tank containing the liquid and refill it with new liquid once the tank has emptied. Users have been able to openly buy liquid flavours and nicotine either pre-mixed or that they mix up themselves. The charge from the battery that heats up the metal coil that vapourises the liquid can also be adjusted.

If these liquids had nicotine in them, they have always been illegal in Australia. But the wholesale diversion of many health department staff to COVID duties across three years has seen only a few prosecutions occur, with thousands of retailers openly breaking the law knowing they had a homeopathic probability of being prosecuted.

The Labor government, in collaboration with six Labor-led states and Tasmania will see a dramatic change in this. We are seeing momentum in significant seizures and fines. In May a Queensland retailer had 45,000 vapes seized and was fined $88,000 including court costs. The Therapeutic Goods Administration has recently issued infringement notices of $105,600 (July 2023), $558,840 in June, $16,000 in May, and $66.600 in April.

The word on the street is that in the hiatus period before widespread raids on retailers commence, vape sales are booming with customers being told “you’d better stock up now because all this is going to end pretty soon”.

When this happens and personal supplies are exhausted, there will be thousands of mod/tank systems lying unused in drawers around the country with other redundant technologies like VHS tapes, film cameras, Walkmans, cassette tapes and passé gaming units.

The Therapeutic Goods Administration was able to make regulations on nicotine because nicotine when sold outside of cigarettes is classified in Australia as either a poison or a therapeutic substance. So it has no remit to make recommendations about mods/tanks themselves other than in relation to approved NVPs that would be approved for sale as prescription items.

This raises the serious question about whether the government ought to consider adding mods/tanks systems to the prohibited imports list. This can be done simply by the stroke of a pen under customs regulations. Few Australians would realise for example, that cat and dog fur products, dog collar protrusions, electronic insect swatters, kava and ice pipes are among all 71 prohibited import items that were included without extended parliamentary or community debate.

Use of mod/tank systems by children in Australia is rare, with disposable sickly sweet flavoured vapes overwhelmingly dominating. But adult use is far more common.

What’s the problem with mods/tanks?

The primary issue has always been the devices themselves. Users are able to control the power settings. More power means that more ‘juice’ is being consumed, i.e., increasing exposure to the nasties. In less complicated devices, more power also translates to higher temperatures which creates even higher levels of by-products of thermal degradation (e.g., acetaldehyde, acrolein, formaldehyde and others).

But if there is no legal access to liquid nicotine, then why should anyone worry? Why would anyone bother buying one of these devices from now on? It’s common to see bongs, pipes and other dope-smoking paraphernalia on open display in shop windows. So why not also allow mods/tanks to be imported and displayed in shop windows?

The outstanding concern here is that mod/tank vaping apparatus can be used to vapourise other drugs which according to this San Diego drug treatment centre can include cannabis. LSD, GHB (gamma hydroxybutyrate) and ketamine. This is far from rare. A 2022 Kings College London survey found that 14.7% of people aged 18+ in the UK had ever vaped a non-nicotine drug, with nearly 1 in 56 (1.8%) currently doing it. In 2019, 3.9% of 19-24 Americans ( 1 in 26) had vaped cannabis in the last 30 days. I’ve found no data on other drug vaping by under 18s, which of course does not mean it is not happening.

As of February 18, 2020 a total of 2,807 people had been hospitalised in the USA for vaping product use-associated lung injury (EVALI). 68 people died. Of these:

- 82% reported using THC-containing products; 33% reported exclusive use of THC-containing products.

- 57% reported using nicotine-containing products; 14% reported exclusive use of nicotine-containing products.

Here’s a sad example of a young woman “cannamom” who never “leaves the house without carrying one of my looper vapes” to smoke weed.

No data appear to be available on the incidence of health incidents following vaping other drugs, but the World Drug Survey included questions on it in a recent survey.

Australia’s vaping advocates have repeatedly emphasised their unswerving, inviolable conviction that vaping nicotine is all but benign. They have also warned vapers never to vape other substances. In doing this they have wedged themselves on this issue. They regularly retort that no one has ever died from vaping nicotine. With smoking-caused chronic diseases like respiratory, cardiovascular and cancers taking decades to manifest after smoking uptake, that would be entirely expected. The median age at which asbestos-caused, invariably fatal mesothelioma is diagnosed in Australia is 77, with first exposure typically 40-60 years earlier. Vaping has been widespread for less than a decade in Australia.

Mod/tank systems were invented and marketed to facilitate nicotine vaping. But like a Trojan horse, they have also enabled widespread vaping of non-nicotine drugs which have killed and seriously harmed thousands in the US alone. Vaping advocates just shrug at this and argue that this legacy is all irrelevant to nicotine vaping. But it’s not.

Collateral damage (what economists call negative externalities) from intended use is routinely considered in all formal risk assessments in health and community safety. For example, gun control policy considers gun misuse, not just approved uses in hunting and target shooting; DDT was widely used in Australia in agriculture and termite control where it was extremely effective, but banned in 1987 because of its collateral residual health risks to humans. Vaping advocates sneer at efforts to reduce kids’ access to vapes, sarcastically bleating “won’t someone please think of the children” memes, as they do all they can to wreck policies designed to do just that.

So here again, don’t hold your breath waiting for any calls for open vape systems to be banned from import or sale. Vaping leaders will unashamedly walk on both sides of the street, warning about the risks of vaping other drugs while demanding that the open systems being used should be openly available to make some nicotine vapers happy.

Update 8 Aug

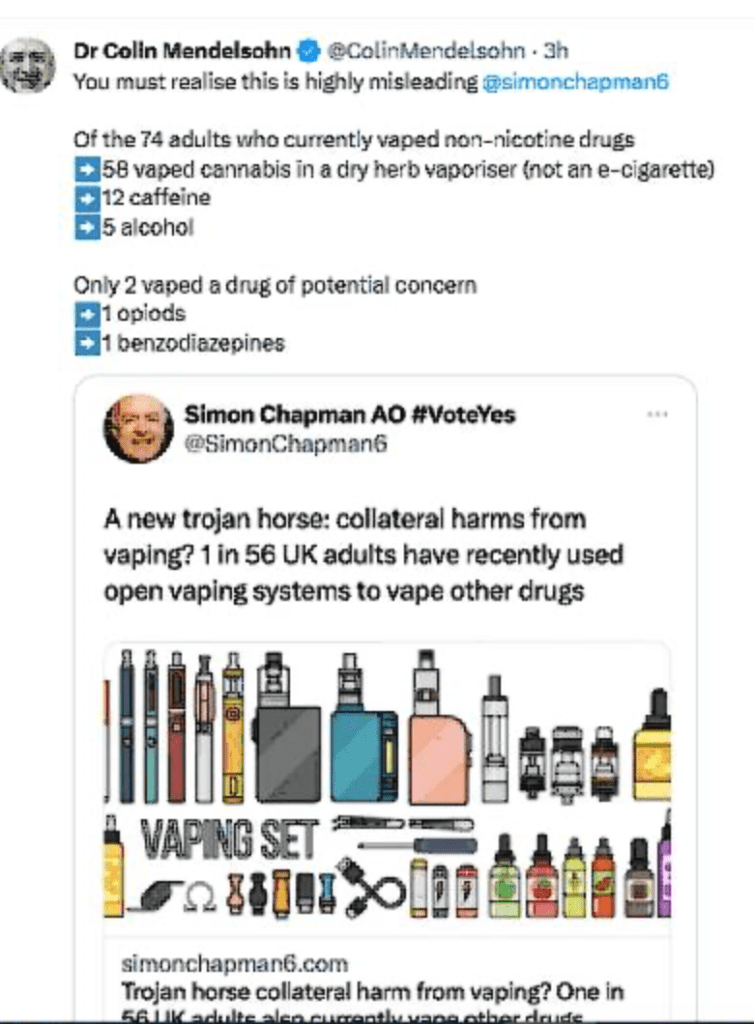

It seems my blog passed the proverbial scream test with flying colours. “Dr Col” Mendelsohn the vaping promoter was quick out of the blocks in apoplexy tweeting that it was “highly misleading” for me to cite this UK study showing that 1 in 56 UK adults had vaped drugs other than nicotine in the past 30 days. He implied that vaping cannabis in “a dry herb vaporiser”, and vaping caffeine or alcohol were not of “potential concern”, words he agreed applied to vaping opioids and benzodiazapines.

So what is the evidence that vaping caffeine and alcohol are of no concern? This site outlines the risks of vaping alcohol. And what about caffeine? In December 2019, the Australian government approved the banning of the sale of pure caffeine and foods and beverages containing high concentrations of caffeine. This followed the death from caffeine toxicity of a 21 year old Blackheath man, Lachlan Foote, after drinking a protein drink with added caffeine powder on New Year’s eve. A single teaspoon of caffeine can be fatal, containing the equivalent of between 25 to 50 cups of coffee. But hey, nothing to worry about in sticking caffeine in your vape tank and pulling anyone’s guess of whatever amount of vapourised caffeine deep into your lungs, according to our expert, Dr Col.

Dry herb vaporisers are already on sale in Australia (see this example). A search on PubMed for “dry herb vaporiser” (or “dry herb vaping”) shows that no studies appear to have been published in indexed journals on the toxicology of emissions from dry herb vaporisers. So how do these differ from nicotine vaporisers?

A Hong Kong supplier is helpful here:

“A popular misconception is that dry herb vaporizers are the same as e-cig type of vapes. Dry herb vaporizers are not the same as e-cigs. Unlike e-cigs, dry herb vaporizers are not intended to deliver nicotine or other substances found in tobacco-containing cigarettes. Instead, they are used to inhale various substances that are found in a plant called cannabis, which is better known as marijuana.”

So have we all got that? The only difference appears to be that one is used for vaping nicotine and the other for vaping cannabis.

So just who is being misleading here?