Photo credit: Gerd Altman, Pixabay

[updated 21 Feb, 2025]

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s triennial National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS) published its most recent report in February 2024. The latest data were collected in 2022-23, with the report offering a wealth of comparative data across past surveys. The latest survey saw more than 21,000 people provide information.

Smoking is a major focus of the NDSHS and in this blog, I’ll highlight some of the gains where undeniable progress has occurred, and look at a claim that the government is haemorrhaging taxation revenue so badly from a drift to illicit duty-not-paid cigarettes that it needs to change course.

A recent segment on ABC TV’s 7.30, on illicit tobacco sales in Australia saw the journalist set up the piece by stating “There is universal acknowledgement that the black market poses a serious threat to reducing smoking” and that there are “fears that Australia’s mission to reduce the daily rate [of smoking] to just 5% by 2030 is going backwards.”

As we will see shortly, there is no evidence in the NDSHS that Australia’s progress in reducing smoking is “going backwards”. Anything but. First, we need to clarify what data are critical to any examination of that proposition.

What is smoking prevalence?

The expression “smoking rate” is commonly used to refer to smoking prevalence – the percentage of people in a population who smoke. Typically, this is a composite figure of those who smoke daily and less than daily, even if only occasionally. The NDSHS counts daily smoking as well as two measures of occasional smoking (less than daily, but at least weekly; and current occasional – less than weekly) in what it counts as “current smoking”. Current smoking thus includes people who might smoke very occasional cigarettes—even less than once a month.

Falling smoking prevalence is a product of two phenomena: (1) reductions in the proportion of people who start smoking and (2) smoking cessation (quitting) by smokers. Smoking prevalence alone does not give a clear picture of whether the rate of quitting is changing.

The quit proportion

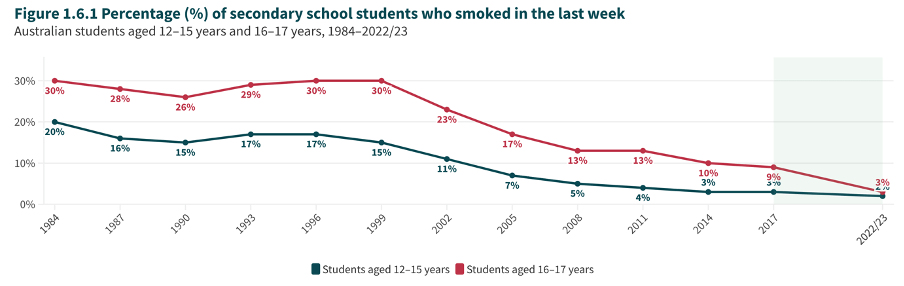

Getting a handle on how a country is travelling with policies, laws and campaigns designed to increase quitting is not best measured by looking at prevalence data, because this is powerfully influenced by changes in the uptake of smoking, mostly by young people which has been in continuous free-fall for 25 years since 1999.

Source: https://www.tobaccoinaustralia.org.au/chapter-1-prevalence/1-6-prevalence-of-smoking-teenagers

Instead we look across time at a measure known as the “quit proportion”. This is the proportion of people who have ever smoked but no longer smoke (ex-smokers as a proportion of current smokers + ex-smokers). Changes in the proportions of people who have never smoked and who are dragging smoking prevalence down are thus accounted for here by only considering those who have ever smoked.

Below are the data on changing smoking prevalence and quit proportions between 1998 and 2022-23. When a quit proportion increases across time, this is rock-hard evidence that quitting is increasing throughout the population.

| Tobacco smoking status, people aged 14 and over, 1998 to 2022–2023 | |||||

| YEAR | NEVER SMOKERS | EX- SMOKERS | DAILY SMOKERS | CURRENT SMOKERS | QUIT PROPORTION (~) |

| 1998 | 49.2 | 25.9* | 21.8 | 24.8 | 51.1 * |

| 2001 | 50.6 | 26.2 | 19.4 | 23.1 | 53.1 (0.2) |

| 2004 | 52.9 | 26.4 | 17.5 | 20.6 | 56.2 (3.1) |

| 2007 | 55.4 | 25.1 | 16.6 | 19.4 | 56.4 (0.2) |

| 2010 | 57.9 | 24.0 | 15.1 | 18.1 | 57.0 (0.6) |

| 2013 | 60.1 | 24.0 | 12.8 | 15.8 | 60.3 (3.2) |

| 2016 | 62.3 | 22.8 | 12.2 | 14.9 | 60.5 (0.2) |

| 2019 | 63.1 | 22.8 | 11.0 | 14.0 | 62.0 (1.5) |

| 2022-3 | 65.4 | 24.1 | 8.3 | 10.5 | 69.7 (7.7) |

| Change 1998 to 2022-23 | + 32.9% | -6.9%# | – 61.9% | -57.7% | +36.4% |

Source: Table 2.1 in smoking table at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/illicit-use-of-drugs/national-drug-strategy-household-survey/data

*1998 saw a change in the earlier definition of current and former smoking (to exclude those who have smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes (or equivalent) in their lifetime

#The decline in the prevalence of ex-smoking over this period results importantly from the reduced uptake of smoking, resulting in fewer ever-smokers in the population from which people may or may not quit.

A helicopter view of this data since 1998 shows (1) continual growth in the proportion of never smokers (up 33%), (2) continual falls in both daily smokers (62% fewer) and (total) current smokers (58% fewer) and (3) a continual rise in quit proportions, with a 36% increase since 1998.

Moreover, the latest data point (2022-23) shows that compared with the previous survey data year (2019) the absolute falls in the prevalence of daily smoking (-2.7%), of current smoking (-3.5%) and the growth in quit proportions (+7.7%) were all at record levels. These are hard measures of smoking declining in the population and of quitting increasing.

So in what universe could anyone look at these data and point to anything but clear and significant progress? Glass-half-empty critics claiming that other comparable nations are doing better than Australia often neglect to mention that “smoking” is measured differently in different national smoking surveys (Australia counts use of any combustible tobacco product as “smoking”, with some nations only counting cigarettes); conveniently leave inconvenient data off their gotcha graphs to show unflattering progress; and focus on the rate of recent falls overseas rather than acknowledging that Australia remains on the front row of the grid, with only New Zealand ahead showing recent 15+ smoking prevalence of 8.3%.

Here are the bottom lines from the most recently published national data on smoking:

Australia (2022-23 14+) 10.5% current & 8.3% daily — all combustible tobacco products

Canada (2022 15+) 10.9% current in last 30 days, 8.2% daily, cigarettes only

Europe (all EU members 2019 15+) 18.4% daily, cigarettes only

New Zealand (2022-23 15+) 8.3% current & 6.8% daily –all combustible tobacco products

UK (2023 16+) 10.5% current cigarettes only

USA (2021 18+) 14.5% any combustible product, 11.5% cigarettes

New Zealand’s success is something of an outlier among Canada, the EU, the UK and the USA which like it, have had years of liberal access to vapes but not seen anything like New Zealand’s fall in smoking while vaping shot up. This may have had something to do with the (now abandoned) high profile policy in New Zealand to radically restrict the supply of tobacco products to create a “Smokefree Generation”, and all the publicity that accompanied that proposal.

In any event, the NDSHS is a cross sectional repeated time series survey with different respondents, not a longitudinal cohort of the same people, so causal conclusions about the contributions of particular polices or campaigns to the changing data cannot be drawn, only speculated.

Growth in illicit tobacco sales

On the ABC 7.30 program, James Martin, a criminologist from Deakin University, opined that an alleged massive growth in purchasing illicit tobacco commenced “in the last 18-24 months” i.e. since 2022, the date when the latest NDSHS survey was conducted. So if large numbers of smokers were switching to cheap illicit tobacco and not quitting at that time as Martin argued (“now that’s not due again primarily to people quitting smoking but rather taking that money and instead of paying tax on it and paying for a legal product that is going straight to the hands of organised crime”) then how do we begin to explain the substantial leap in the quit proportion for that same period in the table above? (The NDSHS counts smokers of licit or illicit tobacco as smokers.)

Asked whether the drift to purchasing far cheaper illicit cigarettes would “bring more people back to smoking” (i.e. ex-smokers and never smokers) Martin agreed that as smokers were price sensitive “the widespread availability of black market tobacco … would be encouraging people into smoking.” Remarkably, when asked whether the government should lower the tobacco tax rate, he agreed they should.

Here, Martin’s position is intriguing: he agrees cheap illegal cigarettes encourage smoking, but says the government should reduce the taxation rate to … encourage smokers back to duty-paid smoking?

Illicit tobacco sold in Australia is a very expensive tobacco product by world standards for black market tobacco. A typical price commonly reported in Australia is $20 per illegal pack, making it still more expensive than tax-paid tobacco products in the US and many European countries. Tobacco tax drives up the price of illicit tobacco, with vendors calibrating it against what local smokers pay for licit cigarettes. If tax were reduced, the price of both legal and illicit tobacco would fall.

On the program, Health Minister Mark Butler commented on this suggestion by noting that there were no significant organisations –such as the World Bank, the IMF or the WHO which argued that governments should reduce tobacco tax because of the threat of illegal tobacco.

In summary, the NDSHS data provide no support at all for the doomsaying suggestion that Australia’s “mission to reduce the daily rate to just 5% by 2030 is going backwards.” Nor to Martin’s ominous – some might say rather theatrical – prediction that “At some point the federal government will have to admit that they’ve got the policy wrong and they will have to change tack.”

There are clearly lots of smokers buying the illegal, duty-not-paid cigarettes, but the net result has not seen any evidence of increased uptake of smoking, nor of reductions in quitting. We have seen the opposite, which has been the decades-long intent of policy on tobacco tax rises.

The government is losing considerable tobacco tax revenue and retailers of duty-paid tobacco and cigarettes may be seeing falls in sales, but when it comes to tobacco, Australian governments since the 1970s have explicitly introduced polices and campaigns designed to do just that and the falls shown are consistent with that policy intent.

But aren’t smokers cash cows to governments ?

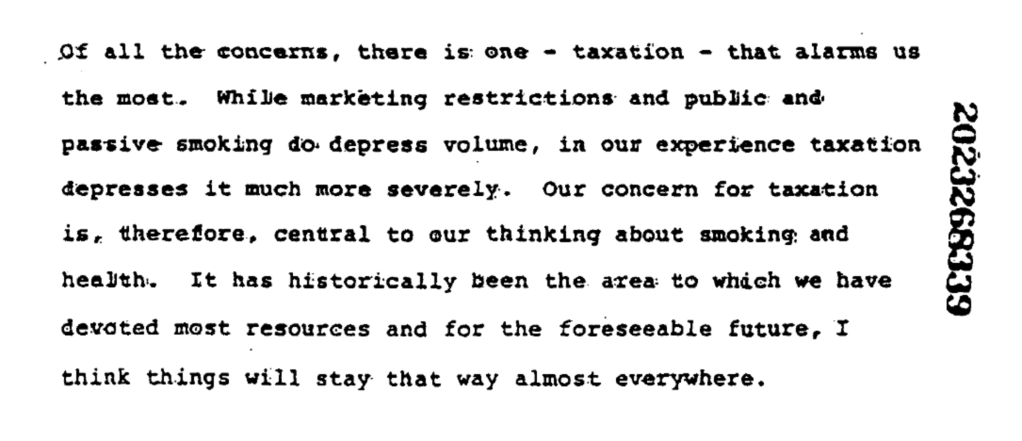

Social media has always been full of cynical smokers arguing that governments don’t really want to reduce smoking because it would kill a goose that keeps laying large golden eggs. This is a truly bizarre claim when we consider all the tobacco control policies governments have implemented over the decades, designed explicitly to reduce smoking and successfully doing so. These policies have long caused apoplexy in the local and international tobacco industry, which is really all we need to know about how damaging they are to sales.

Philip Morris International internal top management document 1985

But when someone doesn’t smoke, they don’t calculate each night how much tobacco tax their non-smoking status has deprived the government that day, take out scissors or matches and destroy that money to spitefully deprive grasping governments of revenue.

Instead, we spend the money we have not spent on tobacco on other goods and services, nearly all of which attract a 10% goods and services tax, and create multiplier economic benefits in the economy. Certainly, with tobacco excise tax being additional to GST, smoking does indeed lay extra golden tax eggs.

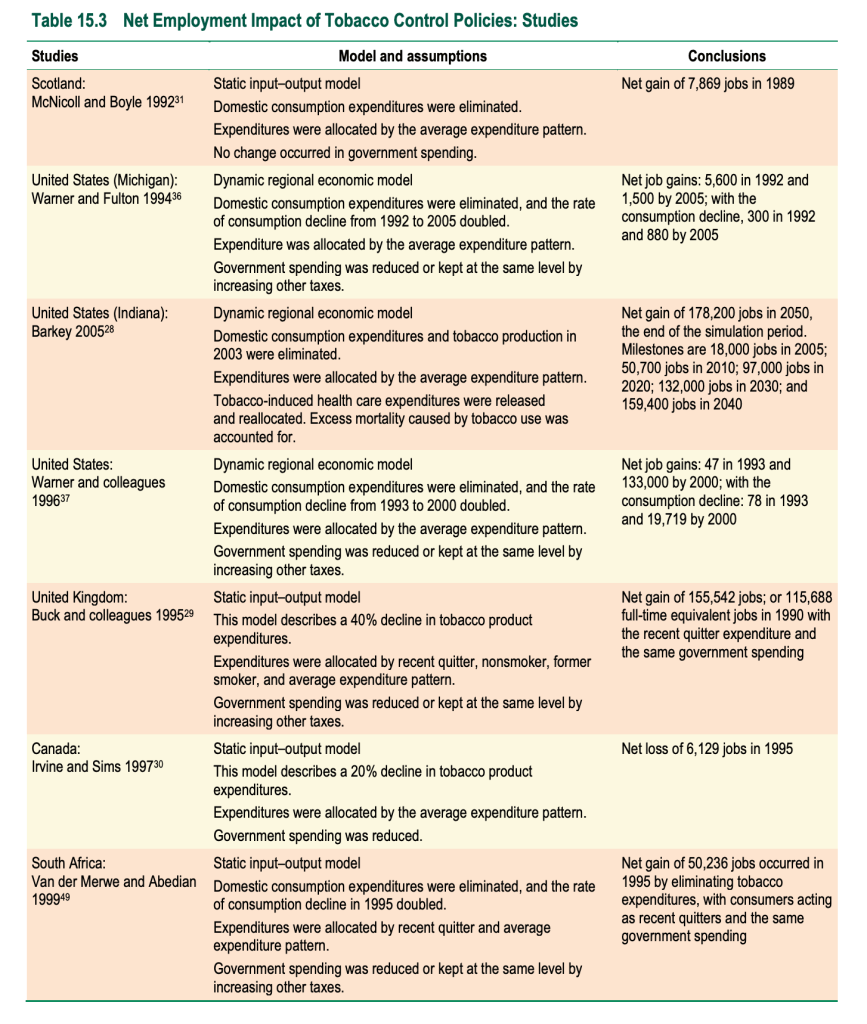

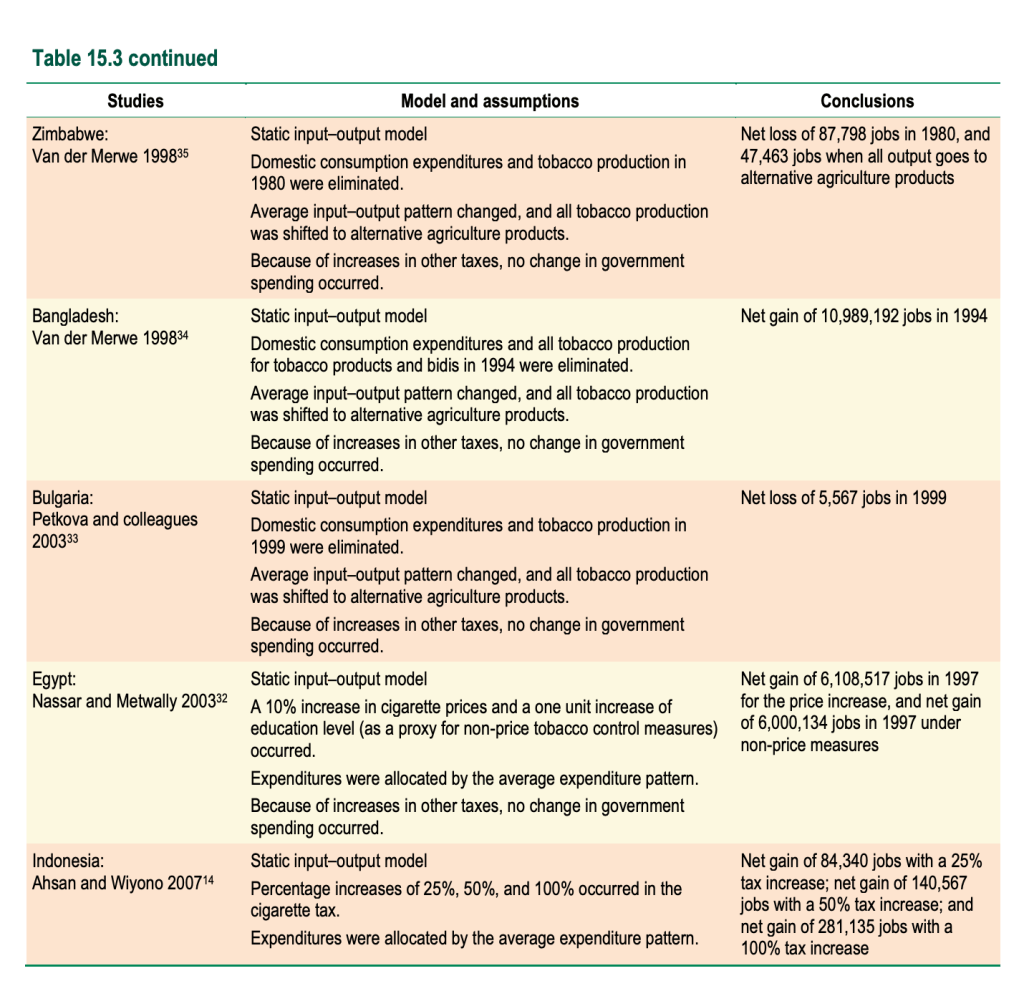

But in fact spending money on tobacco has been shown to be one of the worse things a consumer can do to benefit an economy. This 2020 review concluded that “In nearly all countries …” effective tobacco control “policies will have either no effect or a net positive effect on overall employment because tobacco-related job losses will be offset by job gains in other sectors.” For example, this US paper by two health economists modelled the large economic benefits to Michigan if it were to be (hypothetically) entirely smokefree. Other studies have reached similar conclusions about the net employment impact of reduced smoking (see table)

Source: https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/sites/default/files/2020-06/m21_15.pdf

Professor Ken Warner from the University of Michigan, summed all this up in a heavily cited paper in 2000.

“when resources are no longer devoted (at all or as much) to a given economic activity, they do not simply disappear into thin air—the implication of the industry’s argument. Rather, they are redirected to other economic functions. If a person ceases to smoke, for example, the money that individual would have spent on cigarettes does not evaporate. Rather, the person spends it on something else. The new spending will generate employment in other industries, just as the spending on cigarettes generated employment in the tobacco industry. Studies by non-industry economists in several countries have confirmed that reallocation of spending by consumers quitting smoking would not reduce employment or otherwise significantly damage the countries’ economies.”

This point was also made in 2001 in the British Medical Journal by Clive Bates, a long time commentator on tobacco control.

“taxes are just a recycling of money in the economy. If there was no smoking … consumers would be spending their money on other things (which would also be taxed), and the government would be raising the budget it needs through other taxes, with no change in the total tax burden … Taxes just cannot be counted as a benefit in the same way that healthcare costs or savings can be counted.”

Further, all three tobacco transnationals selling in Australia are unlisted on the Australian stock exchange, have not manufactured tobacco products in Australia since 2016, importing all their cigarettes and roll-your-own tobacco into Australia, dragging on the balance of trade. They have tiny workforces here and repatriate all profits to their international headquarters. Tobacco has not been legally grown in Australia since the 1990s, so there is no agriculture or manufacturing sectors contributing to the Australian economy. These are further major considerations when considering the economic benefits of tobacco control.

Pigouvian taxes (eg: on sugar, carbon, alcohol, tobacco) are fundamentally about correcting an externality – some behaviour that a government wants to see change. That’s different from our other taxes, where the goal is raising revenue. With Pigouvian taxes, we want to change behaviour. With revenue-raising taxes, we don’t want to change behaviour.

Indeed, in the case of tobacco taxes, governments want revenue to fall, because when matched by falling smoking prevalence, it means the policy is working as intended.

Martin a “Tobacco Harm Reduction Advisor”

James Martin is listed on Harm Reduction Australia’s website as one of 15 board members, with his profile dated March 1, 2020. He is described as a “Tobacco Harm Reduction Advisor.” However the Australian Charities and Not for Profit Commission (ACNC’s) details on HRA do not show him as a “responsible person” (“Generally, a charity’s Responsible People are its board or committee members, or trustees.”)

Martin’s research output on his university page shows he has published 24 papers and book chapters since 2013. Not one of these concern tobacco or vaping. But with no published research track record in any aspect of tobacco control, he apparently thinks differently to the significant national and global organisations which have never recommended lowering tobacco taxes. And to the governments of 183 nations representing over 90% of world population which are parties to the global Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, which gives prominent emphasis to tobacco tax in reducing smoking.

Martin recently described Clive Bates on Twitter as “a master”, yet appears to diverge from him when it comes to tobacco tax matters. Perhaps he needs to widen his understanding of tobacco control and start his peer reviewed contributions to the field if he wants to offer advice that might be taken seriously.