It’s often said that the devil has all the best tunes. But when it comes to supporting and comforting those facing imminent death, those with religious faith have a huge walk-up start on us non-believing atheists in the trove of things that you can say to a dying person or their families afterwards.

This was first driven home to me when a close colleague in the US started up a blog to keep his many friends informed about the progress of his advanced cancer, which took his life about nine months after diagnosis. He was Jewish, but in the years I knew him I sensed he was not very observant. Every post he made on the blog attracted many responses letting him and his family know that people were praying for him, that God would surely show mercy and give him strength and so on.

These people were telling him they were going well beyond just being concerned about his progress, or that they held him in their thoughts; that they knew he was courageously “fighting” his disease, or was showing enormous character in writing the blog in the face of his illness. In praying they were somehow suggesting that this news would be received as helpful. The subtext was that their prayers might somehow turn the progress of the cancer around. They were offering hope against hope that their prayers would not only bring comfort but would work.

There are many who seriously believe that if they and others pray for a sick or dying person, that this will actually make a difference. They have faith that the power of prayer is real and consequential.

A Cochrane systematic review of trials of intercessory prayer’s impact on health outcomes completed in 2009 reported on:

“whether there is a difference in outcome for people who are prayed for by name whilst ill, or recovering from an illness or operation, and those who are not. Both groups of people still received their usual treatment for their illness. Ten trials were found which randomised a total of 7646 people. The majority of these compared prayer (for someone to become well) plus treatment as usual with treatment as usual without prayer. One trial had two prayer groups, comparing participants who knew they were being prayed for with those who did not. Another trial prayed retroactively, randomising people a month to 6 years after they were admitted to hospital. Each trial had people with different illnesses. These included leukaemia, heart problems, blood infection, alcohol abuse and psychological or rheumatic disease. In one trial people were judged to be at high or low risk of death and placed in relevant groups.

Overall, there was no significant difference in recovery from illness or death between those prayed for and those not prayed for. In the trials that measured post-operative or other complications, indeterminate and bad outcomes, or readmission to hospital, no significant differences between groups were also found. Specific complications (cardiac arrest, major surgery before discharge, need for a monitoring catheter in the heart) were significantly more likely to occur among those in the group not receiving prayer. Finally, when comparing those who knew about being prayed for with those who did not, there were fewer post-operative complications in those who had no knowledge of being prayed for.

The authors conclude that due to various limitations in the trials included in this review (such as unclear randomising procedures and the reporting of many different outcomes and illnesses) it is only possible to state that intercessory prayer is neither significantly beneficial nor harmful for those who are sick. Further studies which are better designed and reported would be necessary to draw firmer conclusions.”

So what can those of us who cannot with any sincerity say that we are praying for a dying person or believe in any sort of afterlife say that might be welcome and comforting to the dying and their loved ones? When I’ve had occasion to write or speak to a friend who is dying, I’m terribly conscious that they might be clinging to even thin threads of hope that they will miraculously survive. So the last thing I’d want to do at such a moment is to callously assume the dying friend should, however rationally, abandon hope.

On the night my own mother died, her last words to me and my father gasped through her feverish hypoxia from cancer in her lungs, was that she would tell her GP the next day that she wanted to take a final chance with a new drug trial. To pull that last hope from her would have been unspeakable. (see p69 here)

The imminence of a person’s death makes me always think about what I imagine they might like to hear from those who are important to them. When they are gone, we do this in absentia at memorial services and wakes which can be very emotional and cleansing. I always think, gee, wouldn’t it have been lovely for them to have attended their own memorial and heard people say all these heartfelt things when they were alive.

What I wrote to a friend

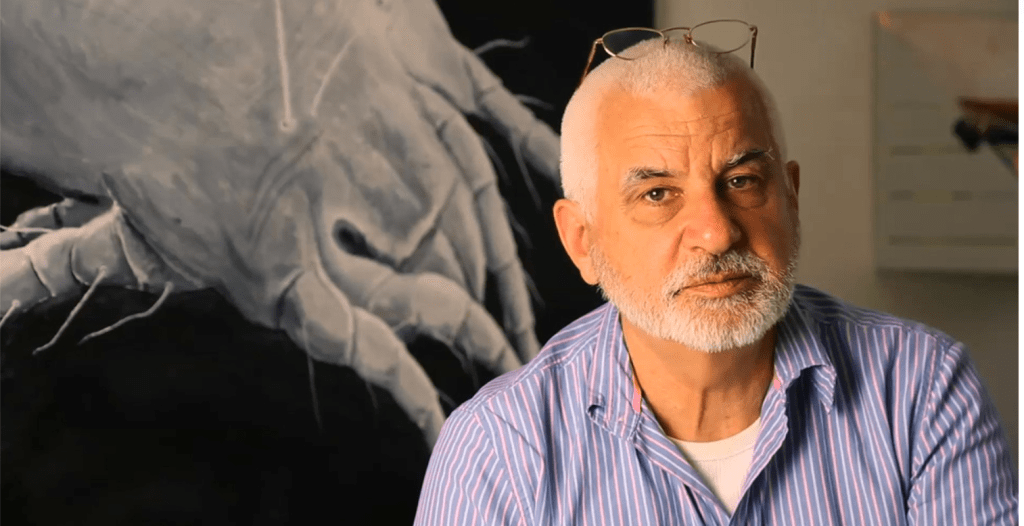

On June 28 this year, we lost a beautiful friend, Euan Tovey, to pancreatic cancer. Late in 2023 when it seemed likely that he might not even make Christmas, his family contacted his best friends and asked them to make a contribution to a book they would assemble before he died. I thought this was a brilliant idea where all those important to him would tell him what he had meant to them. He lived to read the book.

We had spoken at length in his months after diagnosis about his prognosis. He knew he would die, but wanted to live as comfortably as possible for as long as he could. We discussed voluntary assisted dying. He too was an athiest, so our conversations were devoid of all you would expect.

I wrote the following for the book to underline the boundless affection I felt for him across our friendship.

Euan, my dear friend

I knew of you before I met you. My best recollection of how we finally met was that we both quite often seemed to be in need of coffee around the same time. So it was one day in Ralph’s café at the university that you introduced yourself as we waited.

You must have known of me too and seemed as curious as I was delighted. We get instant impressions of some people, while others need to percolate across many encounters before any sense of who they are begins to form.

You are one of the instant category. If a Martian asked me to explain what a “transparent person” means, I would walk them around to your place, knock on the door and introduce you. You are so much of an open book, and it’s that which I think is both the foundation and the glue that has bound us these past years, opening up all the enchanting things that I’ve found in you.

Please spare me from stitched up people for even a moment longer than circumstances sometimes necessitate. But your voice on the phone or the thought of a night out with you and Lib has always put a big smile on my face.

Your candour, friendliness, sparkle and warmth were there right from the start. I knew pretty much immediately that I liked you. You would be someone who if we passed on campus or in the street, I’d always want to stop for a chat.

Those brief encounters at Ralph’s cafe went on for a few years before we began seeing each other in the way we do now. When I retired in 2016, I sensed that your proximity a few streets away would foment us seeing each other more and more.

It didn’t harm things that Trish was all a-tremble with excitement at getting to know your very famous wife. But you quickly became the icing on that wonderful cake for her. As gigs followed dinners, we seemed to enter your inner circle of special friends, being invited to your end-of-year drinks and even deeper into the rituals of your family on-line quiz during COVID. We were very touched and delighted by all this.

You rapidly became a couple we wanted to share around too. I recall directing you to Martyn and Mim’s house at Rous Mill in the hinterland of Lismore. Martyn called me right after you left and said “wow, what beautiful people those two are.”

The Friday walkers reacted the same way. Everyone felt you both were such a perfect part of the group. Everyone was so pleased Lib could come to the dinner on Saturday. You were very missed.

Trish quickly added you to her very short but highly esteemed list of ”real men” who can make and fix stuff. “Why can’t you be more like Euan, Simon? He’d know how to fix this.”, she’d regularly say or imply, with her withering accuracy.

When I had COVID in December last year, you thoughtfully dropped off an air purifier you had knocked up with a few sheets of plywood, some industrial strength rubber bands and god knows what other gadgetry inside. We marvelled at your home recording studio, your mask prototypes and of course your retro-fitted round Australia HiAce shaggin’ wagon.

Here, we also noted more than once, your allusions to your private ribaldry. “That pair!” we’d say with huge affection.

It wasn’t all good. I confess to being very disappointed that your Kiwi accent is barely noticeable. I am a bit of a chameleon with accents, quickly adopting the accents I’m in conversation with. The south island Un Zud accent is particularly infectious.

I am also very envious of your luxurious mane and your bold shirts.

But what I will miss about you more than anything Euan, is that I know I will have lost what I unequivocally feel is a man who is one of my very closest friends. I have many female friends, but not so many males I feel very close to.

I’ve sometimes been asked by interviewers doing profile pieces “if you could change anything in your life until now, what would it be?” I often answer that I so regret not starting to watch AFL and my beloved Swans until about 20 years ago. I wasted 30 years watching the sporting equivalent of hillbilly music in following rugby league, when I could have been watching the balletic spectacle and poetry of AFL.

But I know with absolute certainty that I will from now often say that I lost all too early a very dear friend with whom I had a near-perfect rapport, tastes and love of conversation. He could even cook superbly. We only knew one another well for about 10 years. I will miss you deeply, my dear friend. I so wish we had met 20 years ago. I feel cheated.

Trish and I hope you will take lots of comfort from knowing that we will fold Lib closely into our lives after you are gone. We have loved our growing friendship and count you both among our dearest friends.

I came home yesterday from tennis to find Trish sitting on the lounge sorting through her recordings of her singing lots of songs with her uke. The one that was playing as I entered the room was Aretha Franklin’s I say a little prayer. Listen to it here.

We both have no time for religious malarky, so you know I have not been beside the bed praying for you. But the religious imagine they have a direct line to the fixer man, and so are doing something actively virtuous.

We’ve been saying our little secular prayers for you, so Trish’s song seemed apposite (of course, extend the sentiments in the words wider than it being a romantic love song).

I’ll end with the (English) words to a Herman Hesse poem, Bein Schlafengehen, that Richard Strauss set to music in his incomparable Last Four Songs. This Elizabeth Schwartzkopf version is the best.

We played it at my mum’s funeral. The words and music always bring me to tears of sadness and joy at my many memories.

Going To Sleep

Now the day has wearied me.

And my ardent longing shall

the stormy night in friendship

enfold me like a tired child

Hands, leave all work;

brow, forget all thought.

Now all my senses

long to sink themselves in slumber.

And the spirit unguarded

longs to soar on free wings

so that, in the magic circle of night,

it may live deeply, and a thousandfold.

Hermann Hesse (from Richard Strauss’ Last four Songs)