Late last month, Philip Morris International tweeted one of its daily attempts to convince the world that it is now a health promotion company, firmly aligned with global public health to try and reduce the disease and death caused by tobacco use. Its mainstay, cigarettes, kill two out of every three long term users.

The company is aggressively marketing its heat-not-burn product IQOS (see footnote below) in several markets and Altria, which owns Philip Morris USA, recently invested $US12.8 billion in the tearaway e-cigarette market leader, Juul. PMI has bankrolled the establishment of the fully “independent” Foundation for a Smokefree World with a grant of $US960 million dollars over 12 years in a classic exercise in astroturfing its messages to also come from a third party.

The Foundation has attracted incendiary criticism since it was first announced. See here, here, here, here, here and here, as just a few examples.

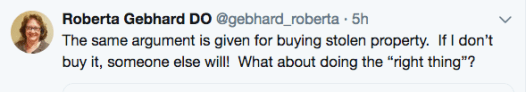

Last month a PMI tweet stated “If we stopped selling cigarettes tomorrow, someone else would take our place”.

This was clearly a response to what any review of how its “we’ve changed” message is traveling would have undoubtedly identified as its most hobbling Achilles’ heels: its long-standing track record in both attacking tobacco control policies that threaten to actually reduce smoking (high cigarette tax, plain packs, graphic health warnings, smoking restrictions), and its on-going aggressive global marketing and promotion of its cigarettes.

For example, in Indonesia, the world’s fourth most populous nation where it is almost compulsory for men to smoke, the tobacco industry exploits this smokers’ paradise. A pack of cigarettes can sell for less than a small bottled water, tobacco advertising virtually wallpapers the entire country and non-smoking areas are uncommon and mostly ignored. Philip Morris owns the local manufacturer Sampoerna, which controls about one-third of the massive market there. In 2011, a Sampoerna advertisement proposed “Dying is better than leaving a friend. Sampoerna is a cool friend”. In 2015, the company began aggressively promoting its U-bold brand, a “stronger flavoured” brand, often code for higher yielding tar and nicotine brands.

In July, 2018, a legal action brought by the Philippine Tobacco Institute (PTI), representing Philip Morris and other tobacco manufacturers, succeeded in preventing an ordinance being implemented in Balanga City, Luzon which would have banned smoking and the sale, distribution and promotion of cigarettes within the 80-hectare University Town and its kilometer radius. A press report stated that “PTI had argued that Philip Morris Philippines Manufacturing Inc. would lose P15 million in sales due to the city’s ban.”

In 2018, the company opened a new $30m cigarette factory in Tanzania

These are hardly actions compatible with ad nauseum statements from company that it wants smokers to quit.

The tweeted admission “If we stopped selling cigarettes tomorrow, someone else would take our place” disrobes the entire charade. The “we’ve changed” emperor now quite clearly has no clothes.

Let’s pick the statement apart, one ethically bankrupt sub-text at a time.

Like a wolf outside a henhouse, Philip Morris has gushed an incontinent deluge of claims that it really, really wants smokers to switch to its alleged low risk products. But never once in all this has it set any target dates. Nowhere can we find when the company plans to actively take steps to end its own role in encouraging and promoting smoking and attacking policies known to reduce smoking. Will this happen in 5 years? 10 years? 30 years? Never?

All we know now is that it won’t happen “tomorrow”. And the great beauty of it never being tomorrow, is that tomorrow never comes.

We might think they were serious if they were to, for example, voluntarily move their cigarette products to dull plain packaging and add large pictorial warnings, or declare that they wre going to voluntarily stop all cigarette advertising in nations where it is still allowed, or axe their “Mission Winnow” sponsorship of Ferrari in the F1 Grand Prix and Ducati in the Moto GP when Mission Winnow’s advertising livery is red and white, coincidentally we can be certain, the same colours as Marlboro.

But hell might freeze over before they did any of these things.

The company is not simply going to passively sit by and watch smoking prevalence continue to head south by taking its feet off its marketing accelerators or slamming them hard in concert with public health on the tobacco control policy brakes. It has said and done nothing to indicate that it won’t continue to do what it can to preserve and expand its cigarette sales.

PMI’s statement requires those reading it to understand that the company has been called out by critics to show that they are being serious about wanting to actively end smoking. But by invoking the “someone else will do bad things if we stopped” they seek to make a virtue out of knowingly and purposefully continuing to do the wrong thing.

Their pitch here is like a brazenly misbehaving 5 year old who knows he is doing something wrong, but says to the teacher “why should I stop? Why pick on me? Everyone else is doing it too!” Or a drug dealer saying to the court “yes, I was cutting my heroin with cheap adulterants that put all who used it at extra risk, but that’s what my competitors are all doing too, and I just needed to keep up with them price-wise or go under. Please sympathise with my situation!”

As I wrote in 2014:

“My wife is a primary school teacher with 35 years experience. She has often described incidents where 5-9 year olds with poorly developed moral compasses have been caught red-handed bullying, stealing, cheating or lying but unblinkingly deny it regardless of the evidence in front of them. More than once, she’s suggested that such a child might one day make an ideal applicant for a job in a tobacco company.

Globally, different legal, moral and religious codes tend to share basic principles when it comes to how to deal with those who have done serious wrong. Sentencing often takes note of evidence of contrition and civilized societies and judiciaries tend look for five broad pre-conditions in considering punishment”

- Full public acknowledgement of the misdeeds and harms caused

- apologising for these harms

- promising never to repeat them

- making good the damage done, and

- undertaking some form of public penance to symbolise your changed moral status.

Like many caught-out five year olds and recidivist adult sociopaths, the tobacco industry has done none of these things. Its corrective advertising is being done reluctantly after 15 years of legal kicking and screaming, while schmoozing with the global corporate social responsibility movement, publicizing its donations to carefully selected charities and just getting on with trying to sell as much tobacco as possible, regardless of the misery it causes.

They have all the ethics of a cash register.”

At least cash registers don’t pretend to be something they are not.

Footnote: a just published report comparing the impact of IQOS with cigarette smoke on human lung cells concluded “IQOS exposure is as detrimental as cigarette smoking and vaping to human lung cells. Persistent allergic, smoke or environmental-triggered inflammation leads to airway remodelling/scarring through re-organisation of ECM and airway cell proliferation, and mitochondrial dysfunction plays a pivotal role in this process. These are the principal causes for airflow limitation in asthma and COPD.”

[updated 24 Jan 2020]

Source: Sydney Morning Herald

Source: Sydney Morning Herald