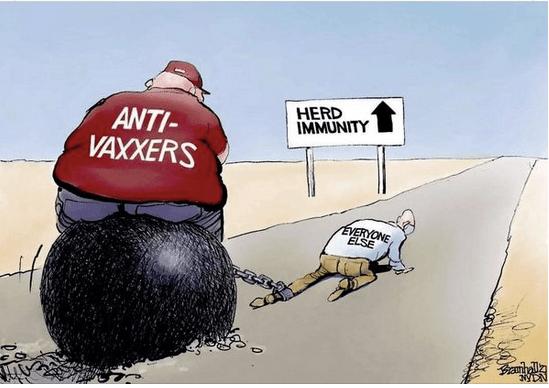

This week’s Guardian Essential Poll had some very disturbing news for all of us hoping that Australia will pull itself out of the basement of nations with high COVID-19 full vaccination levels. Just under half of respondents to the poll (47%) said they would be willing to get the Pfizer jab but not AstraZeneca. Another while 24% are willing to get either, and only 3% are willing to get the AstraZeneca vaccine but not Pfizer. But here’s the clanger: 14% — 1 in 7 of us — remain resolved that they won’t be getting either.

With paediatric vaccinations, today we have national complete immunisation rates at 92.% for 2 year olds and 95.2% for 5 year olds. These are the rates that should be also possible for COVID-19.

These spectacularly good rates rates are a function of blanket vaccine availability and decades of targeted efforts to reduce a multitude of cultural, geographic and educational barriers. But they also reflect decades of efforts by many of the infectious disease epidemiologists, psychologists and educators who have become household names through their daily TV and radio presence since the pandemic broke in March 2020. Many of these people have spent years raising public awareness of the benefits of vaccination, putting the very small risks that exist into perspective and discrediting misinformation spread by dedicated anti-vaccination fruitcakes.

What sort of messaging cuts through most?

Australia has long been a world leader in public awareness campaigning across a wide range of health issues. I worked on Australia’s first major mass reach, well-funded health warning campaign, Quit. For Life (1980-82). We ran ads like these, the most famous being the Sponge ad made by Sydney advertising director John Bevins, where a hand wrung out a sponge oozing with black tar into a beaker with the explanation that this was this was the amount of tar that the average smoker pulled through the filter into their lungs in a year. The quitline rang off the hook.

These ads worked wonders. In Sydney where the ads were run, 23% of a cohort who were followed up 12 months later had quit compared with just 9% in Melbourne where the campaign was not being run.

The Every Cigarette is Doing You Damage campaign (started in 1997) with its unforgettable ad showing white, gelatinous atheroma (plaque) being squeezed from an aorta turbo-charged the downward fall in smoking. Research trialing various candidates for graphic health warnings on packs rapidly discovered that cheery positive messages about not smoking being wonderful, sporty and healthy rarely cut it while tough, unforgettable realism did. And remember actor Yul Brynner spoke from his grave after dying from smoking caused lung cancer saying “now that I’m gone, I tell you don’t smoke”?

Professor Melanie Wakefield’s group from the Cancer Council Victoria is a global leader in health campaign evaluation and strategic research for campaign development in health. An evaluation of the impact of different styles of Australian quit smoking advertisements looked at the differential impact of ads predominantly evoking fear, sadness, hope, or evoking multiple negative emotions (i.e., fear, guilt, and/or sadness).

Their 2018 paper concluded “Greater exposure to hope-evoking advertisements enhanced effects of fear-evoking advertisements among those in higher SES, but not lower SES areas. Findings suggest to be maximally effective across the whole population avoid messages evoking sadness and use messages eliciting fear. If the aim is to specifically motivate those living in lower SES areas where smoking rates are higher, multiple negative emotion messages, but not hope-evoking messages, may also be effective.”

The pioneering anti-smoking ads were the vanguard for several decades of gloves-off, see-once-and-never-forget campaigns in Australia. Millions of saw and have never forgotten the HIV/AIDS Grim Reaper ad (1987), hot-wiring demand for condom use in causal encounters ever since. Road safety campaigns in several states showed the carnage of drink driver and speed. Examples were vignettes of grieving drivers after realising they’d killed someone and exploding dropped watermelons simulating massive head injury from a head going through a windscreen. Annual NSW road fatalities per 100,000 population fell from 28.9 in 1970 to 4.4 in 2019. Each new policy introduced was accompanied by often hard-hitting warning campaigns.

There have been highly memorable campaigns about melanoma and sun tanning, preventing scalding in kids from boiling pots on stoves, wearing bicycle helmets and fire prevention, to name a few.

Old school experimental psychologists have tut-tutted for years about all of this, clutching onto a faded dogma dating from studies of dental education from the 1950s where showing pictures of decayed teeth to students made no difference to their brushing behaviour. But meanwhile, ask any ex-smoker why they stopped and there is daylight between their number one reason (worry about health consequences) and whatever else is in second place.

A 2016 meta-analysis of research on the use of fear and scare concluded “Overall, we conclude that (a) fear appeals are effective at positively influencing attitude, intentions, and behaviors, (b) there are very few circumstances under which they are not effective, and (c) there are no identified circumstances under which they backfire and lead to undesirable outcomes.”

So what have governments learned from all this in Australia with COVID-19 in 2021? Instead of massive national campaigning, we’ve seen dreary memos-to-the-public style ads advising that COVID is highly infectious and deadly, and that vaccination is very important. These are in scintillating writing, with all the magnetism of wallpaper and bring messages that you would needed to have been asleep in a cave on Mars for 18 months to have never heard.

We also had an actress rigged up on a ventilator gasping for breath in a bed. This drew instant criticism from critical care clinicians who were angry at the implication that patients in hospitals would be lying in terror without being intubated and sedated. The ad seems to have quickly disappeared, thankfully. This was an object lesson in how not to use scare in persuasion.

The recent momentum toward COVID-19 vaccination passports is very welcome. While there are many who never plan to travel overseas and rarely go to the cinema or restaurants, if app-based passports are required to get into shops, bars, football games, the TAB and the rest this will doubtless drag many vaccine refusniks to get jabbed.

Please, let’s get serious and see some significant government investment in developing messaging that will erode vaccination apathy and hestitancy, and bolster public momentum toward zero tolerance for those too self-absorbed to play their part in ending lockdown and reducing death and serious illness from this pandemic We did it for drink driving. We did it for indoor smoking. We can do it for COVID-19.

See also:

Is it unethical to use fear in public health campaigns? WordPress 11 Aug 2018

Should those avoiding AstraZeneca vaccination because of the clotting risk also avoid having an anaesthetic? WordPress Jun, 2021

Eight common excuses for not being COVID-19 vaccinated and what you can say that might help. WordPress 27 May, 2021

With the risks of AstraZeneca blood clots being tiny, what explains COVID19 vaccine hesitancy? WordPress 23 May, 2021

A reverse white feather? Let all who are COVID19 vaccinated wear a badge proclaiming and normalising it. WordPress 21 May, 2021

The ethics of shaming prominent COVID-19 mask opponents. WordPress 26 Jul 2020.

How can we erode self-exempting beliefs about COVID-19 contagion and isolation that might subvert flattening the curve. WordPress Apr 19, 2020.