This week, the journal Addiction published a letter signed by 6 high profile researchers, each with histories of working with tobacco companies on putatively reduced harm products. Their brief letter sought to “discuss” the ethical issues, as they saw them, that justified their remunerated research engagement. But it contained little more than several glib assertions.

While 181 nations have ratified the WHO’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, with its Article 5.3 setting out guidelines for limiting tobacco industry interference with tobacco control (“There is a fundamental and irreconcilable conflict between the tobacco industry’s interests and public health policy interests”), a small number of researchers apparently believe they can rise above such concerns.

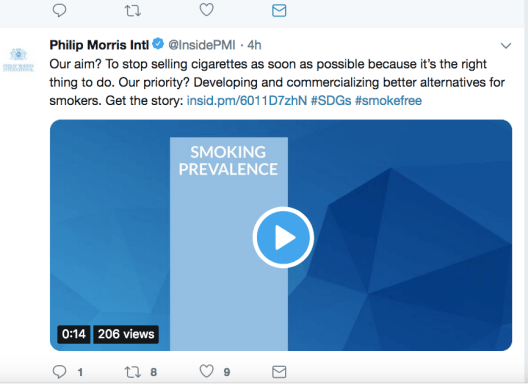

Their letter comes at a time when nearly all tobacco companies are adding so-called reduced risk products to their product portfolios. Some, like Philip Morris are engaging in “we’re changing” charm offensives claiming they are trying “to stop selling cigarettes as soon as possible”.

Ever since the bad news began rolling in from the early 1950s about the inconvenient problem of the very nasty harms smoking causes (latest estimates are that two in three long term smokers will die of a smoking caused disease, translating to some 7 million deaths a year), the industry has pursued a public agenda of announcing successive generations of allegedly reduced harm products. Unfortunately, every one of these crashed as false hopes. All were primarily designed to keep nicotine addicts loyal to the companies’ evolving products and to dissuade people from quitting, as hundreds of millions around the world began doing in increasing numbers from the early 1960s, the great majority without any assistance and often without much difficulty.

No need to quit, when you can keep smoking a “reduced risk” cigarette?

No industry likes seeing its longest and most loyal customers dying early. They’d far prefer that they lived to consume and be contributing cash cows for as many years as possible. There is also no industry more loathed and mistrusted than the tobacco industry. Against this, the harm reduction agenda represents a trifecta of hope for Big Tobacco: it’s a kind of perpetual holy grail, never reached but always sought, with the promise of seeing smokers living and consuming longer. It’s also a way of enticing new generations of users into the market who each time swallow the hype about radically reduced risk products. And it carries hope of eroding the industry’s on-going corporate pariah status, with its attendant risks of attracting sub-optimal staff indifferent to working in a killer industry. It’s a virtue signalling cornucopia that keeps on giving.

Enter e-cigarettes

E-cigarettes and heat-not-burn products (ENDS or Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems) are the latest harm reduction debutantes. The size of the popularity wave they are riding in several nations puts these products in the league of two previous, disgraced heavyweight champions of harm reduction: filter tips and so-call light and mild, cigarettes. Filters are almost universally still used today in cigarettes, but with 7 million deaths a year still occurring, it’s a bit like saying that arsenic is less harmful than cyanide, thanks to filters. Because of compensatory smoking, lights and milds were declared misleading and deceptive descriptors by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission in 2005 and outlawed. Tobacco companies in the USA are currently running court-ordered corrective advertising, including messages about the lights and milds scam.

The rise of ENDS has been accompanied by a chorus of Big Tobacco CEOs proclaiming that they mark the beginning of the end of smoking. “Look what we are doing.” they gush “We are transforming ourselves into companies that are saving lives! We are investing billions into research, development, production and marketing of these new products.”

With their new health promotion vocation, they have tried to cosy up to governments, the WHO and sadly, to researchers like those who signed the letter in Addiction.

The Jekyll and Hyde defence

The authors of the letter in Addiction state that they “limit our work with the industry to projects involving reduced-risk products.” This argument is a kind of Jekyll and Hyde defence. It invites readers to consider that tobacco companies produce both morally defensible and indefensible products, and that it is ethically unproblematic for a scientist to have supportive dealings with those representing the Dr Jekyll persona, but self-evidently unethical to do anything to support murderous Hyde characters.

The unavoidable, blindingly obvious problem here of course, is that Jekyll and Hyde are the same person. Prisons are full of people who at their trials presented outstanding employment records, character references, and receipts for generous charity donations, but who had feet of clay and committed heinous deeds. In the corridors of tobacco companies there are divisions of both Jekylls and Hydes. The two camps may have little to with each other (BAT’s “science” twitter feed @BAT_Sci daily parades the work of its busy harm reduction product staff, but I’ve never seen mention of what its legions of cigarette division chemist staff are up to).

But on the floors that house those in the executive who pull the strings for the entire companies, they know exactly how the company bread is buttered and what the future vision looks like. And for all the sloganeering about the end of smoking, that future has, as it has always been, cigarettes right at the very front of the business model.

PMI’s global market is dominated by cigarettes.

BAT’s 2018 half yearly report could not have been more emphatic on this from its opening paragraph “Our strategy is to continue to grow our combustible business while investing in the exciting potentially reduced risk categories of THP, vapour and oral. As the Group expands its portfolio in these categories, we will continue to drive sustainable growth.” (my emphases)

A senior Philip Morris International spokesman, Corey Henry, told the New York Times in August 2018 “As we transform our business toward a smoke-free future, we remain focused on maintaining our leadership of the combustible tobacco category outside China and the U.S.”

Philip Morris USA’s website candidly speaks of “making cigarettes our core product”.

Reduced risk products instead of or as well as cigarettes?

The Addiction letter authors wrote “If the tobacco industry seeks to make money by making reduced risk products instead of [my emphasis] more risky products, we fail to see this as a menace to public health.”

Yes, I’m afraid they do fail to see. Put simply, there is no evidence – apart from an incontinent river of public declarations – that any tobacco company is taking its foot off the twin business-as-usual accelerators of massively funded marketing of combustible tobacco products (chiefly cigarettes), and continuing efforts to discredit and thwart policies known to have an impact on preventing uptake and promoting cessation.

In recent years companies like BAT and Philip Morris have been relentless in seeking to dilute, delay and defeat any policy posing any threat to their tobacco sales. This is not the behaviour of an industry earnestly trying to get all its smokers to quit. Witness their massive efforts to stop Australia’s historic plain packaging legislation. Witness their years’ long efforts to stop Uruguay’s graphic health warnings. As recently as December 2016, BAT’s lawyers wrote this appalling letter to the Hong Kong administration trying to stop graphic health warnings going ahead. This was from a company which, published in its 2016 financial results statement a call to “champion informed consumer choice”.

Attacking tobacco tax

British American Tobacco’s twitter feeds relentlessly highlight seizures of illicit tobacco. The sub-text for these is that tobacco tax is so high that it is fueling demand for cheaper, illicit tobacco which evades tax. Joining the dots, the proposal here is that governments should stop raising tobacco tax (and perhaps even reduce it) to perversely “help” smokers buy the company’s brands.

In nauseatingly unctuous displays of civic-mindedness, the companies publicly wring their socially responsible hands about smokers having to interact with criminal tax evaders, unknowingly channeling their tobacco purchasing money into terrorism, and depriving national treasuries of much-needed revenue.

All this neatly avoids the public understanding that tobacco companies have used tax rises as air cover to add to their own margins by raising the prices they charge retailers who in turn pass on these increases to smokers. For example, In Australia from August 2011 to February 2013, while excise duty rose 24¢ for a pack of 25, the tobacco companies’ portion of the cigarette price (which excludes excise and GST), jumped $1.75 to $7.10. While excise had risen 2.8% over the period, the average net price had risen 27%. Philip Morris’ budget brand Choice 25s rose $1.80 in this period, with only 41¢ of this being from excise and GST. (see p77 here)

These public displays also keep attention away from the large body of evidence across many years that shows the tobacco industry has long supplied tobacco products to agents in knowledge that these products would enter the illicit, tax avoiding market.

The Philip Morris fully-funded “Foundation for a Smokefree World” has recently awarded New Zealander Marewa Glover $1m to advance harm reduction globally among indigenous peoples. Glover has been a frequent written and vocal critic of tobacco tax, claiming it is ineffective in reducing demand. This contrasts to the overwhelming consensus of evidence about the role of tax in reducing demand. Price elasticity is why all tobacco companies (just like those in every industry) engage in price discounting: smokers smoke more when prices fall, and less when they rise.

In 2011, BATA’s Australian CEO David Crow told a Senate committee “We understand that the price going up when the excise goes up reduces consumption. We saw that last year very effectively with the increase in excise. There was a 25 per cent increase in the excise and we saw the volumes go down by about 10.2 per cent; there was about a 10.2 per cent reduction in the industry last year in Australia.”

All but one of the authors of the Addiction letter are from the USA. Professor Robert West, editor of Addiction, has recently drawn attention to the propensity of American researchers for US parochialism. Looking outside of the US border, we see rampant cigarette promotion still happening wherever possible, particularly in low income nations. A moment’s searching finds examples like the Philip Morris’ controlled Indonesian Sampoerna company, with around a third of the country’s cigarette sales, promoting “stronger” cigarettes on the crest of a 15% industry-wide increase in smoking in the world’s fourth most populous nation. Or evidence of ubiquitous selling of single cigarettes across Africa and promotions near schools.

What could it do?

If Big Tobacco was sincere in its claims it wants to stop selling cigarettes there is much it could do. It could immediately stop all advertising and promotion of tobacco products around the world. It could voluntarily introduce the world’s best practices in graphic health warnings on packs (every company makes decisions every year about how its packaging will look). It could stop supplying illicit trade with tobacco products (currently estimated at one third of all illicit trade), knowing the importance of this in supplying very low income smokers with cigarettes that allows them to keep smoking and hopefully graduate to company brands.

Of course, it will do none of this, continuing instead to endlessly witter its sanctimonious claims about getting out of cigarettes but doing nothing to demonstrate that it is. What it is doing, is to hide behind the weasel words that it will get out of selling cigarettes “as soon as possible”. That’s about as meaningful as saying “when hell freezes over”.

In this, it contrasts with sections of the motor vehicle industry and some governments over the transformation of motor vehicles from being powered by fossil fuels and moving to electric power, in concert with goals to move power generation to renewables. Volvo has announced that 50% of its vehicles will be electrically powered by 2025. By 2017, 10 nations had set dates for the end of fossil fuel car sales. More will follow. No tobacco company has set any target dates.

Over decades, we have seen Big Tobacco’s response to any proposal that threatens their bottom line. Any government announcing that it would no longer allow combusted tobacco to be sold would see every stop being pulled out by the industry to prevent this. But meanwhile the industry, hand-on-heart, assures us all that it really, really wants smoking to end.

And do they really reduce harm?

And then, at the end of the day, all this requires that we all acquiesce and accept that so-called reduced risk products will, in fact, be found to actually reduce risk after years of use. The diseases caused by smoking are chronic diseases (pulmonary, cardiovascular, cancer). For each of these, many years pass between the uptake of smoking across a population and evidence of rising disease incidence.

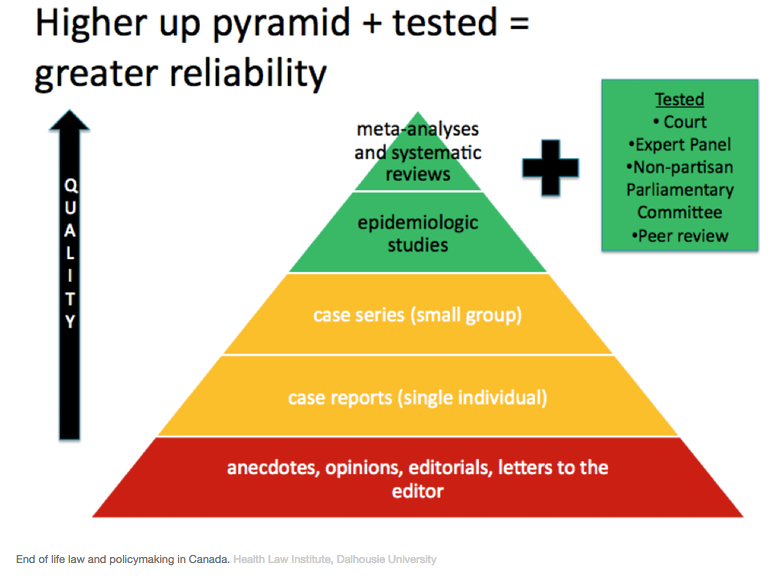

The seminal January 2018 report of the US National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine repeatedly concluded that the quality of evidence now available that e-cigarettes actually reduce health risks was either non-existent, low or limited (see health effects conclusions here) because of the insufficient time that large numbers of people have been vaping.

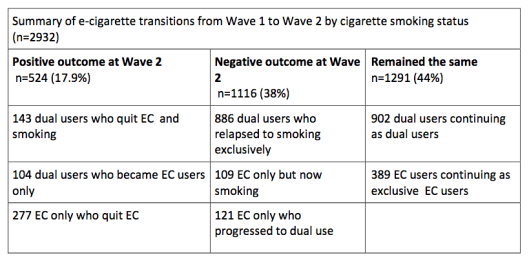

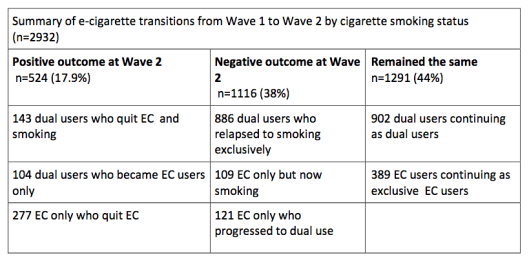

There are many reasons to expect that e-cigarettes may indeed cause less disease than cigarettes. But we know from recent data from longitudinal samples that by far the largest proportion of e-cigarette users continue to smoke (“dual users”); that the reduction in the number of cigarettes that they smoke each day is trivial (see Table 3 here); that reducing (rather than quitting) smoking confers little risk reduction; and that for every one e-cigarette user who has a positive outcome by quitting smoking, more than two continue smoking and vaping, or relapse totally to smoking.

Source: Coleman et al (2018)

Moreover, if we add the dual users who relapsed, the once exclusive e-cigarette users who took up smoking, and the dual users who just kept on smoking and vaping, this important study shows that 12 months on, for every e-cigarette user who benefited by quit smoking and/or e-cigs, 4.6 e-cig users relapsed to smoking, took up smoking or were held in dual use. Little wonder that tobacco companies are wildly enthusiastic about these products.

The 6 authors of the letter state that they are comfortable in working for the industry because “the FDA considers the tobacco industry legitimate, why should we not do so?” The FDA is not directly funded by the tobacco industry, but is regulating it, so there is a world of difference here. This assertion merely acknowledges that tobacco industry manufactures products that are legal to sell if meeting standards being developed by the FDA.

There is much research undertaken on illicit drugs, but it is not funded by the criminals in charge of the trade. Few sensible people would argue that such research is not very important, but no one would seriously suggest that it would be ethical to accept funding by drug dealers.

Most understand that companies have a corporate interest in funding researchers whose outputs will be useful to them, and not create conflicts with their commercial ambitions. There is a very extensive research literature (eg here) that shows a consistent association between industry funding and research findings that are positive for the funding companies.

This is the reason that all serious journals require full disclosure of funding, and why some journals will not accept papers authored by tobacco industry researchers and why the Cochrane Collaboration insists that a majority of its review authors have no competing interests and refuses to consider reviews funded by commercial interests. For these reasons, mechanisms like mandated hypothecated taxes on the industry to fund external research have been proposed as a way of better ensuring the independence and transparency of such research.

The concerns I have described should suggest that the opprobrium some of the authors have experienced should come as no surprise to them. I would welcome any of them responding to the issues I have raised by using the comments function on this page.