Population-focussed tobacco control in Australia has seen smoking prevalence fall to its lowest ever levels for both adults and teenagers. Teenage smoking is all but extinct – an amazing achievement. This has been driven by 50 years of successful public health advocacy for policies, legislation and campaigns increasing public and political awareness intended to foment declines in smoking. Since the 1970s in Australia, there has been no advocated tobacco control policy that has failed to be taken up by governments. The tobacco industry has lost every battle it fought. All cigarette factories have closed and you seldom see anyone smoking in the street. Smoking is a pale shadow of what it was 40 years ago.

Sitting astride all of this has been the continual and progressive denormalization of both smoking and the tobacco industry. Ninety percent of smokers regret ever starting. There’s no product whose users are so disloyal. All political parties except the hillbilly Nationals refuse to accept tobacco industry donations and would rather be photographed with the Grim Reaper than be seen enjoying tobacco industry hospitality.

But over the 45 years I’ve worked in tobacco control, I’ve lost count of the number of times people have assumed I would want to give my support to some truly loopy and sometimes unethical policies. Four leap out. I’ll briefly outline the first three, then go to town on the why the fourth – censorship of films showing people smoking – is the mothership of muddled thinking, indeed stupidity.

1: Got some new way to quit? Sign me up!

Many assumed that I would want to rush to embrace and recommend almost any agent or process intended to help smokers quit. Rarely did a month pass when I was not contacted by a breathless enthusiast for some new purported breakthrough. These included any new way of consuming nicotine other than smoking (I’m still waiting for nicotine suppositories, but surely it can’t be long); any new drug; any complementary procedure maximally accompanied by soothing, holistic placebo-enhancing mumbo-jumbo and eye-watering costs for consumers; any “professional” intervention featuring the nostrums of doctors, nurses, pharmacists, psychologists and counsellors in clinical, group, on-line or app settings.

A piece I wrote 40 years ago in the Lancet (“Stop smoking clinics: a case for their abandonment” see pp154 here) set out why well-intended dedicated quit smoking centres were distractions from the main goal of reducing smoking across whole populations. They were never going to make any serious contribution to reducing smoking nationally because smoking was so widespread and interest in attending such clinics so low, that impossibly massive numbers of clinics would need to open for them to make a difference.

In 2009, again in the Lancet, I proposed the “inverse impact law of smoking cessation” which states “the volume of research and effort devoted to professionally and pharmacologically mediated cessation is in inverse proportion to that examining how ex-smokers actually quit. Research on cessation is dominated by ever-finely tuned accounts of how smokers can be encouraged to do anything but go it alone when trying to quit―exactly opposite of how a very large majority of ex-smokers succeeded.”

I then quantified this with a look at how research on quitting had become overwhelmingly focussed on assisted quitting, with research into unassisted quitting far less common. This was truly bizarre given that no one disputes that the most common way of quitting used in final successful quit attempts has always been to do it cold turkey. So why not learn more about that and shout it from the rooftops?

My contributions caused apoplexy and multi-signatured condemnations from those who had tethered their career sails to assisting smokers. My 2022 book Quit smoking weapons of mass distraction looked in depth at why professional smoking cessation was dominated by the tiny “tail” of treatments, while the large “dog” of real world unassisted quitting was often denigrated by tobacco treatment professionals and the pharmaceutical industry, for obvious self-interested reasons.

2. The smoker-free workplace

A second perennial bad idea proposed that employers should be allowed to reject applicants (for any job) who smoked, even if they were completely agreeable with smokefree workplace policy and did not want to take divisive “smoking breaks” not available to non-smokers. Henry Ford pioneered early workplace smoking bans in his car factories (see photo below) But a century on, some were now arguing that even if workers smoked entirely in the privacy of their own life, employers could threaten them with unemployment because they smoked.

I made a case against this nonsense in 2005.

Two arguments were typically used by advocates for this policy

1: employers’ rights to optimise their selection of staff (smokers are likely to take more sick leave and breaks)

2: enlightened paternalism (‘‘tough love’’).

The first argument fails because while it is true that smokers as a class are less productive through their absences, many smokers do not take extra sick leave or smoking breaks. By the same probabilistic logic, employers might just as well refuse to hire younger women because they might get pregnant and take maternity leave, and later take more time off than men to look after sick children. Good luck with that argument!

But what about paternalism? There are some acts where governments decide that the exercise of freewill is so dangerous that individuals should be protected from their poor risk judgements. Mandatory seat belt and motorcycle crash helmets are good examples.

It was argued that the threat of ‘‘quit or reduce your chances of employment’’ was founded on similar paternalism. I think the comparison is questionable.

Seat belt and helmet laws represent relatively trivial intrusions on liberty and cannot be compared with demands to stop smoking, something that some smokers would wish to continue doing. By the same paternalist precepts, employers might consult insurance company premiums on all dangerous leisure activity, draw up a check list and interrogate employees as to whether they engaged in dangerous sports, rode motorcycles, or even voted conservative!

Many would find this an odious development that diminished tolerance. There is not much of a step from arguing that smokers should not be employed (in anything but tobacco companies where perhaps it should be mandatory?), to arguing that they should be prosecuted for their own good.

3. Finish the job … ban smoking in all outdoor public areas

When the evidence mounted in the early 1980s that breathing other people’s smoke was not just unpleasant to many but could cause deadly diseases like lung cancer, bans on smoking followed in enclosed areas like public transport, workplaces and eventually the “last bastions” of ignoring occupational health: in bars, pubs and clubs.

Some in tobacco control then excitedly began to argue “why stop now? Let’s extend bans to even wide-open spaces like parks, beaches and streets.” The teensy-weensy problem here was that all the evidence on breathing other people’s smoke being harmful came from studies of long-term exposure in homes and workplaces. There was almost no evidence that fleeting exposures of the sort you get when a smoker passes you in the street is measurably harmful.

So banning smoking in wide-open outdoor spaces was not a policy anchored in evidence about health risks to others.

Accordingly, I advocated for smoking prisoners to be allowed to smoke in outdoor areas, for ambulatory patients and their visitors to be able to smoke in hospital grounds if they chose to and for smoking to be allowed in streets. When I was a staff elected fellow of my university’s governing Senate, I voted against a (failed proposal) for a total campus ban on smoking in favour of having small dedicated outdoor smoking areas (see photo). I set out my concerns in these papers, here, here and here.

This marked me as a heretic for some. But as I argued in one of these “I have had heated discussions with some colleagues about this who are triumphant that the proposed ban [on smoking in prisons] will help many smoking prisoners quit. I agree that it will, and that is a good thing. But so would incarcerating non-criminal smokers on an island and depriving them of cigarettes. We don’t do that not just because we can’t, but because it would be wrong. The ethical test of a policy is not just that it will “work”. In societies which value freedom, we only rarely agree to paternalistic policies which have the sole purpose of saving people from harming themselves if they are not harming others.”

4. Ban smoking in movies, or slap them with box-office killing R-ratings

But true peak silliness in tobacco control advocacy arrived when a small number of people began arguing for all movies which depicted smoking to be either banned, or more commonly, slapped with R (18 and over) classifications, known to severely reduce box office receipts. This threat would see most film producers order their directors to impose on-screen smoking bans.

I first flashed bright amber lights on this idea in 2008. With a US co-author, I followed up with four arguments against this proposal in this PLoS Medicine paper and this response to criticism that followed. Much of our paper was hypercritical of research that purports to show that there is a strong association between kids seeing smoking in movies and their subsequent smoking. Some – including even the World Health Organization – even tried to extrapolate attributable fraction estimates of the number of deaths down the track that this exposure would cause down the track in what was an uncritical orgy of highly confounded leaping from simple associations to causal statements. The huge number of assumptions and uninhibited reductionist reasoning in this exercise was quite extraordinary.

The main problem here was that when characters smoke in films, they do not just smoke: they bring to their roles a constellation of other attributes that are likely to be deeply attractive to youth at-risk of smoking.

As we wrote: “Teenagers select movies because of a wide range of anticipated attractions gleaned from friends, trailers, and publicity about the cast, genre (action, sci-fi, teen romance, teen gross-out/black humour, survival, sports, super hero, fantasy, and so on), action sequences, special effects, and soundtrack. It is likely that youth at risk for current or future smoking self-select to watch certain kinds of movies. These movies may well contain more scenes of smoking than the genres of movies they avoid (say, parental-approved “family friendly,” wholesome fare like the Narnia Chronicles or Shrek).

Teenagers at risk of smoking are also at higher risk for other risky behaviors and comorbidities. They thus are likely to be attracted to movies promising content that would concern their parents: rebelliousness, drinking, sexual activity, or petty crime. … Movie selection by those at risk of smoking is thus highly relevant to understanding what it might be that characterizes the association between young smokers having seen many such movies and their subsequent smoking. Movie smoking may be largely artifactual to the wider attraction that those at risk of smoking have to certain genres of films. These studies rarely consider this rather obvious possibility, being preoccupied with counting only smoking in the films.

By assuming that seeing smoking in movies is causal, rather than simply a marker of movie preferences that have more smoking in them than the movie preferences of those less at risk, authors fail to consider problems of specificity in the independent variable (movies with “smoking”). It may be just as valid to argue that preferences for certain kinds of movies are predictive of smoking. The putative “dose response” relationships reported may be nothing more than reporting that youth who go on to smoke are those who see a lot of movies where smoking occurs, among many other unaccounted things.”

All this was silly enough, but where the silliness became weapons-grade in its over-reach was the way in which some in public health didn’t hesitate to decide they had every right to start urging that governments should censor movies (and presumably theatre, books, art, smoking musical performers) which showed smoking.

We wrote:

“most fundamentally, we are concerned about the assumption that advocates for any cause should feel it reasonable that the state should regulate cultural products like movies, books, art, and theatre in the service of their issue. We believe that many citizens and politicians who would otherwise give unequivocal support to important tobacco control policies would not wish to be associated with efforts to effectively censor movies other than to prevent commercial product placement by the tobacco industry.

The role of film in open societies involves far more than being simply a means to mass communicate healthy role models. Many movies depict social problems and people behaving badly and smoking in movies mirrors the prevalence of smoking in populations. Except in authoritarian nations with state-controlled media, the role of cinema and literature is not only to promote overtly prosocial or health “oughts” but to have people also reflect on what “is” in society. This includes many disturbing, antisocial, dangerous, and unhealthy realities and possibilities. Filmmakers often depict highly socially undesirable activities such as racial hatred, injustice and vilification, violence and crime. It would be ridiculously simplistic to assume that by showing something most would regard as undesirable, a filmmaker’s purpose was always to endorse such activity. Children’s moral development and health decision-making occurs in ways far more complex than being fed a continuous diet of wholesome role models. Many would deeply resent a view of movies that assumed they were nothing more than the equivalent of religious or moral instruction, to be controlled by those inhabiting the same values.

The reductio ad absurdum of arguments to prevent children ever seeing smoking in movies would be to stop children seeing smoking anywhere.”

Despotic and fundamentalist religious governments have huge appetites for censorship (think North Korea and Afghanistan under the Taliban). But in the west, there is a long and often disturbing queue of single-issue advocates who would wish to see greater state intervention in cultural expression. Precedents for such doors to be opened should be treated with great caution. If scenes of smoking should be kept from childrens’ eyes, why stop there?

The slippery slope is today well-oiled in the USA where in a growing number of Republican states a large range of books are being removed from school libraries at the behest of Christian family-values activists.

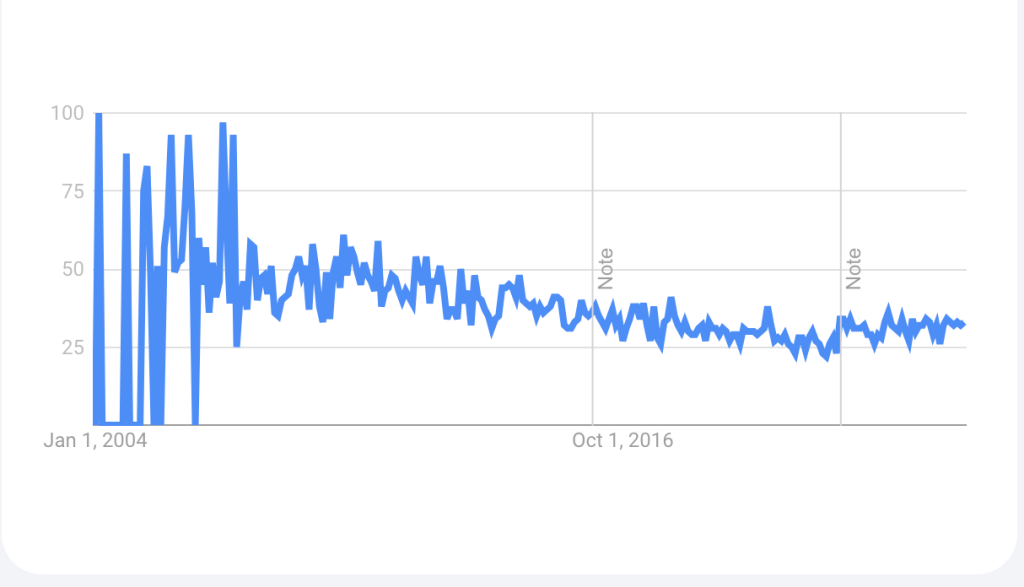

The Google Trends graph below shows that globally the debate about R-rating smoking in movies had a massive rush-of-blood from 2004-2009, with attention waning in the years since. Advocates for censorship and R-rating have succeeded in several national and global agencies endorsing their calls. But significantly, no nation has legislated to R-rate smoking films.

Even if they did, as far back as 2004, 81% of under 18s were allowed by their parents to view R-rated movies in the USA occasionally, some or all of the time. With all the myriad ways available today to view movies on-line, via downloads, movie swapping and piracy, any thoughts that R-rating would achieve anything look increasingly absurd.

The Tobacco In Australia website has a very thorough section on all the debating points relevant to the whole issue.

Google Trends “smoking in movies” 10 Jan, 2023: 2004-present, worldwide