Tags

[extra material added 17 Oct 2024 — see Dai et al below]

By any measure, Ken Warner, Avedis Donabedian Distinguished University Professor Emeritus of Public Health at the University of Michigan, is one of the giants in the history of tobacco control. I have known Ken since the early 1990s, after he editorialised one of my earliest papers. We were both 2003 recipients of the American Cancer Society’s global Luther Terry Medal and have had decades of mutual respect.

He has written a glowing endorsement for one of my books and references for promotions and awards. When I retired from the University of Sydney in 2015, my head of school invited me to select a global figure who could be the main speaker at my festschrift. I didn’t hesitate to name Ken, who gave this lecture after which we spent a few great days on the NSW north coast.

At that time Ken was showing early enthusiasm for the promise of e-cigarettes as a major new weapon in reducing smoking and the diseases it causes. I was far more circumspect, having provided one side of a debate in the BMJ in 2013 and a crystal-balling piece on the promises and threats in 2014.

In the years since, I’ve seen him rapidly firm in his positive views about the public health importance of vaping, In 2018, an internal document from the vapes manufacturer Juul Labs included Ken’s name on a list of ratings of 18 “collaborators” ranking him 7 out of a maximum 10 and noting that he was “positive on all scenarios” about vaping. I was listed as one of 10 “current opponents”.

We have rarely exchanged views on the issues in the nine years since his trip to Sydney, although I have received comments from friends of him eye-rolling when my name has come up. He’s a true believer in vaping, while I’m a sceptical apostate in circles he frequents.

Warner has just published a piece in the American Journal of Public Health titled Kids are no longer smoking cigarettes: why aren’t we celebrating. It’s generally excellent, celebrating the near-to-zero high school smoking rates in the US, and principally attributing the declines to the unabating massive cultural denormalisation of smoking (“The principal answer is a major change in social norms”) This was set in motion by the application of evidence-based policies about what would drive youth smoking down across whole populations. He’s incredulous – as am I – that not more prominence and celebration has been made of youth smoking all but having disappeared.

He declares, and I again agree, that “By any measure, youth smoking has nearly ceased to exist.” The nearing extinction of youth smoking has confirmed tobacco control as the poster-child of chronic disease control. The achievement is precious silverware that has been hard fought for and needs vigilance against both predators and complacency to ensure that it will never rise again.

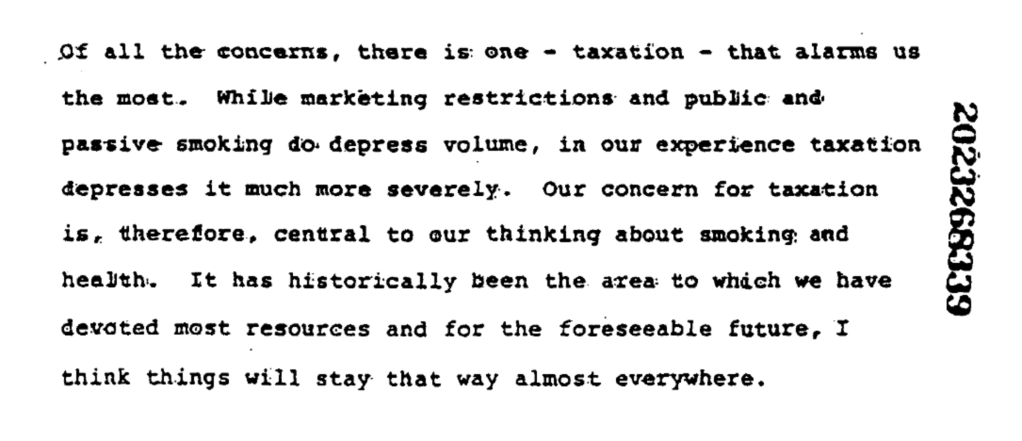

Warner wonders whether the tobacco industry “may be giving up their age-old pursuit of ‘replacement smokers’”, its coded euphemism for recruiting new teenage smokers. Is there anyone who believes that they would find these developments a bitter, force-fed pill that they would dearly love to reverse?

Here are the US data on 8-12th graders’ 30 day smoking.

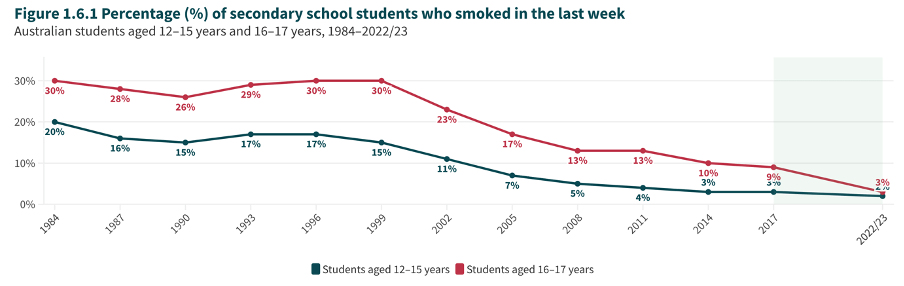

We have a very similar situation in Australia (see chart below), with smoking in the last week falling between 1999 and 2022-23, the latest data year available. The US has seen senior high school prevalence drop like a stone from 36.5% in 1997 to 1.9% in 2023. Australia has seen the same age group’s weekly smoking rate fall from 30% in 1999 to 3% in 2022-23 (monthly smoking is 3.4% (12-15y) and 5.2% (16-17y). The US is thus a little ahead of Australia with teenage smoking, with both nations seeing smoking spiralling toward tiny proportions.

However, there are several points in Warner’s paper which require comment when it comes to some of his assertions about vaping.

Warner’s presentation of the US data frames teenage vaping as predominantly a phenomenon of kids who smoke also vaping. He writes that:

“In 2022, 9% of never-smoking high school students had vaped in the past 30 days, 3% frequently (≥ 20 days). In contrast, 54% of ever-smoking students had vaped in the past 30 days, 34% frequently. Still, that 3% of never-smoking students vape frequently is a legitimate source of concern.”

Here, highlighting the much larger proportions of smokers who vape gives the impression that it’s overwhelmingly school students who have smoked who dominate teenage vaping in the US, with those who’ve never smoked, being comparatively less likely to be vaping.

But looking at the numbers behind these proportionspaints a very different picture.

With never-smoking youth being (by far) in the majority, even small vaping participation rates among them could translate to greater numbers of vapers than among the much smaller proportions of youth who smoke. So here’s how the numbers fall.

The table below constructed from the dataset here by colleague Sam Egger shows that of 15884 students, 1265 vaped in the past 30 days who had never smoked, compared to 931 who had ever smoked. In other words, in terms of sheer numbers, the problem of vaping is worse for the never-smoker group compared to ever-smoker group. So if you saw random student vaping in the US, there would be a 58% (=1265/(1265+931)) probability that this vaper would be someone who had never smoked compared to a 42% probability that it would be someone who had ever smoked.

When it comes to more frequent vaping, this situation is reversed with 58% of those who vaped on ≥20 of past 30 days being ever-smokers (=583/(583+425)) compared with 42% who were never-smokers.

This way of looking at it presents the situation in quite a different light. Focusing on column percentages in the table below frames the situation as very much it being a case of smokers doing the vaping. But focussing on row numbers demonstrates that vaping is very much a more comparable phenomenon between ever- and never-smokers when it comes to actual numbers of youth who are vaping.

In Australia (see Figure 16), more than two-thirds (69%) of 12-17yo school children who vaped “reported having never smoked a tobacco cigarette before their first vape. One in five (20%) students who had never smoked prior to trying an e-cigarette reported subsequent smoking of tobacco cigarettes (i.e., at least a few puffs).”

Vaping by US high school students, 2022 in National Youth Tobacco Survey

| Never-smoke | Ever-smoke | |

| (n=14164) | (n=1720) | |

| Vaped in past 30 days | ||

| No | 12899 (91.1%) | 789 (45.9%) |

| Yes | 1265 (8.9%) | 931 (54.1%) |

| Vaped on ≥20 of past 30 days | ||

| No | 13739 (97.0%) | 1137 (66.1%) |

| Yes | 425 (3.0%) | 583 (33.9%) |

Frequencies are weighted by weights provided by NYTS to account for the complex survey design and to produce nationally representative estimates. Excludes n=234 with missing data on vape or smoke variables

Is vaping by kids all but benign?

Warner’s paper emphasises that vaping is far less dangerous than smoking, and that nicotine in itself in the doses obtained through smoking or vaping is likely to cause inconsequential health problems, apart from the non-trivial economic costs of nicotine dependence. I have several caveats about his summary.

There is no shortage of evidence that vapes deliver often far less of key carcinogens and toxicants than do cigarettes. This evidence includes biomarker research showing that vapers have less of these nasties in their bodies. Warner summarises this as: “In fact, smokeless tobacco products sold in the United States create substantially less risk than does smoking”

But vapes and cigarettes are very different beasts: cigarettes are the Mt Everest of risk but vapes contain chemicals that cigarettes don’t contain, and the puff parameters for vaping are very different from those for smoking.

“the contention that nicotine can damage developing adolescent brains or harm health in other ways”.

Here Warner argues “Most research regarding brain effects is based on animal models but with potential relevance for humans.” Prominent vaping advocates have often ridiculed the relevancy of animal studies for humans, elevating this to meme status in true believers about vaping. But “potential relevance” is surely a huge understatement. Of the 114 Nobel Prize winners in medicine and physiology between 1901 and 2023, 101 (88.6%) used animals in their research. Now what would such eminent researchers know that vape advocates seek to dismiss?

Warner continues: “the lack of evidence of brain damage in previous generations of people who smoked mitigates this concern.”

This is quite a sweeping statement, unreferenced.

It’s been frequently noted that smokers are increasingly concentrated in less educated, economically disadvantaged sub-populations. Low education and low IQ are clearly correlated, so it’s unsurprising that cognitive concerns may be more prevalent in smokers. But there is also significant evidence that smoking may also be causative for cognitive and psychiatric problems.

For example, in this cohort study of over 20,000 Israeli military recruits, analysis of brothers discordant for smoking found that smoking brothers had lower cognitive scores than non-smoking brothers.

This prospective cohort study examined the association between early to midlife smoking trajectories and midlife cognition in 3364 adults (1638 ever smokers and 1726 never smokers) using smoking measures every 2–5 years from baseline (age 18– 30 in 1985–1986) through year 25 (2010–2011). Five smoking trajectories emerged over 25 years: quitters (19%), and minimal stable (40%), moderate stable (20%), heavy stable (15%), and heavy declining smokers (5%). Heavy stable smokers showed poor cognition on all 3 measures compared to never smoking. Compared to never smoking, both heavy declining and moderate stable smokers exhibited slower processing speed, and heavy declining smokers additionally had poor executive function.

In this Finnish longitudinal cohort twin study data (n=4761) from four time points (for ages 12, 14, 17, and 19-27 years) “were used to estimate bivariate cross-lagged path models for substance use and educational achievement, adjusting for sex, parental covariates, and adolescent externalizing behaviour.”

Smoking at ages 12 and 14 “predicted lower educational achievement at later time points even after previous achievement and confounding factors were taken into account. Lower school achievement in adolescence predicted a higher likelihood of engaging in smoking behaviours … smoking both predicts and is predicted by lower achievement.”

In a cohort study of 11 729 children with a mean age of 9.9 years at year 1 Dai et al used structural magnetic resonance imaging measures of brain structure and region of interest analysis for the cortex, 116 children reported ever use of tobacco products. Here’s an edited version of the results and conclusions.

“Controlling for confounders, tobacco ever-users vs nonusers exhibited lower scores in the Picture Vocabulary Tests at wave 1 and 2-year follow-up. The crystalized cognition composite score was lower significantly lower among tobacco ever-users than nonusers both at wave 1 and 2-year follow-up. In structural magnetic resonance imaging, the whole-brain measures in cortical area and volume were significantly lower among tobacco users than nonusers. Further region of interest analysis revealed smaller cortical area and volume in multiple regions across frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes at both waves. In summary, initiating tobacco use in late childhood was associated with inferior cognitive performance and reduced brain structure with sustained effects at 2-year follow-up.”

Nicotine not a culprit?

Warner states that “nicotine per se is not the direct cause of the diseases associated with tobacco. Rather, it causes persistent use of the products that expose users to the actual toxins.” This proposes that nicotine is not a health problem, only a benign vector for health problems.

In 2019 I compiled this selection of research about concerns with nicotine published in notable journals including Nature Reviews Cancer, Lancet Psychiatry, American Journal of Psychiatry, Mol Cancer Res, Critical Reviews in Toxicology, Carcinogenesis, Mutation Research, Int J Cancer, Apoptosis and Biomedical Reports. These concerns are seldom mentioned by those who recite Michael Russell’s dictum that “People smoke for the nicotine but they die from the tar” as a talisman against any expressed concerns about nicotine.

I’ve also listed numerous recent reviews of the emerging evidence about vaping and precursors of respiratory and cardiovascular disease. This evidence hardly describes an assessment of vaping as a benign practice akin to inhaling steam in a shower or having a couple of cups of coffee a day, analogies I’ve heard used by vaping advocates.

Importantly too, there is no mention in Warner’s paper about two key ways in which vapes importantly differ from smoking.

A: Flavouring chemicals in vapes

Flavours are a leading factor that attract and keep people vaping: the beguiling cheese in the nicotine addiction mousetrap. But as has often been pointed out, none of the many thousands of flavours available in vapes have ever been assessed as safe for inhalation. Many of the chemical flavouring compounds in vapes have GRAS (Generally Regarded As Safe) ratings as food and beverage additives for ingestion. But it is elementary in toxicology that different routes of consumption (skin, inhalation, ingestion, rectal insertion) have different risk profiles.

Tellingly, no flavoured inhaled asthma or COPD medicines (used by hundreds of millions globally) have ever been approved by therapeutics regulators anywhere in the world, yet vaping advocates typically shrug dismissively about possible risks in the intensive inhalation of flavours in vapes.

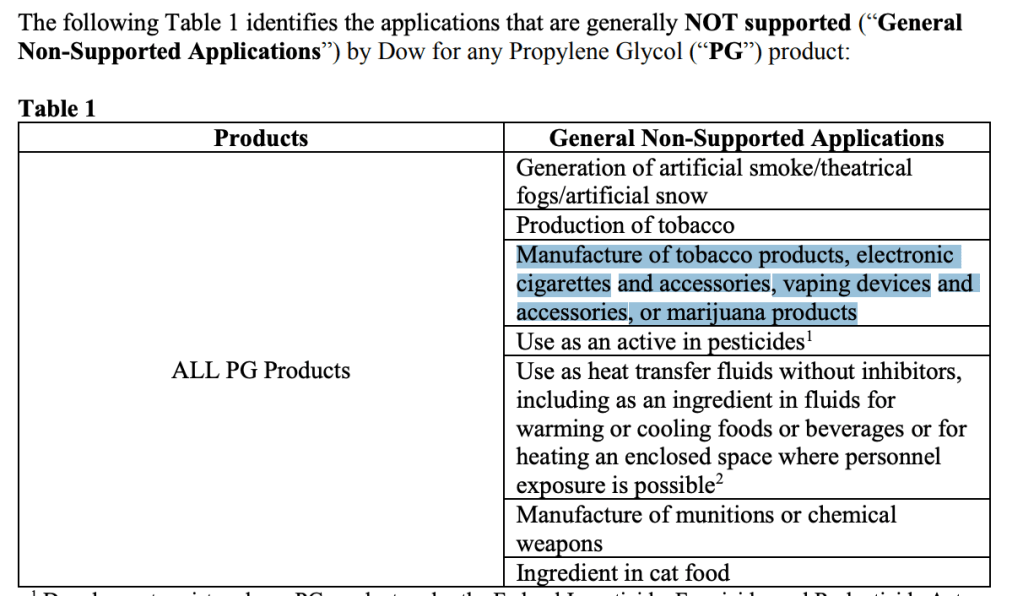

Dow Chemical, a major manufacture of propylene glycol (the most common excipient in vape liquid) in 2019 explicitly named PG in vaping devices and accessories as a “non-supported application”. With the vast earnings potential for Dow in embracing PG in vapes, clearly the risk exposure to the company in doing so must have been assessed as massive.

Warner cites several examples of the public and health professionals holding clearly incorrect views about particular dangers of vaping, as if the jury is already in on the net effects of harm into the future – the whole point with chronic disease control. Yet he sensibly agrees that it is too early to know if there will be any long-term health problems that might arise from vaping. The median age for diagnosis of asbestos-caused mesothelioma is between 75-79. For lung cancer, it’s 71. If putative health problems from vaping have similar latency periods from first exposure to diagnosis, we may have a long wait before this issue is settled.

B: Inhalation frequency

The average daily smoker in Australia in 2022-23 smoked 15.9 cigarettes day and a typical puff frequency per cigarette in leisurely situations is 8.7, giving 138 puffs per day. Observational studies of vapers show that average daily puff frequency on vapes is likely to be north of 550 times. In one study (2016), researchers observed vapers using their normal vaping equipment ad libitum for 90 minutes. The median number of puffs taken over 90 mins was 71 (i.e. 0.78 puffs per minute or 47.3 per hour). Another (from 2023) found those using pod vapes took an average of 71.9 puffs across 90 minutes, almost identical to the 2016 study number.

But of course vapers do not vape across only one continuous 90 minute period each day. No studies appear to have calculated average 24 hour vape puff counts. But if we (conservatively?) assume 8 hours of sleep and 4 waking hours of no vaping, then a person vaping for 12 hours a day at this 47.3 puffs per hour rate, would pull 568 puffs across a 12 hour day deep into their lungs, 207,462 times in a year and 2.075 million times across 10 years.

This compares to daily smokers taking 138 puffs a day, 50,405 times a year and 504,050 times in 10 years: 4.12 times less. Cigarettes and vapes are very different products, but the almost frenzied puff frequency we see with daily vapers where each puff sees excipient chemicals like unapproved flavourants and PG pulled deep into the lungs throughout the day should raise red flags.

Australia’s approach to vaping regulation which I have strongly supported has landed at access by adults only via pharmacies, a ban on the importation of vaping products other than those destined for the pharmacy channel, and truly weapons-grade deterrent penalties for any person or corporation breaching these laws.

This has been the approach governments have long used to regulate access to methadone and other narcotics used in pain control, medicinal cannabis and every prescription pharmaceutical. Despite the demand for these products, no government is planning a free-for-all for these products in corner shops. It is very early days, with major busts of flagrant selling likely imminent. Australia has pioneered several tobacco control policies which have dominoed globally. I expect to see the same happen with our vaping regulations.