ATHRA, a small Australian lobby group for e-cigarettes with a Twitter following today of all of 494 (including many vaping activists from overseas), often argues that smoking prevalence in Australia is lagging behind the US and the UK. Its website states “Australia’s National Health Survey confirms that smoking rates have plateaued in Australia. According to the national survey this month, 15.2% of Australians adults smoked in 2017-18 compared to 16% three years ago.”

“Current smoking” to the Australian Bureau of Statistics means daily smoking plus “other” which means “current smoker weekly (at least once a week, but not daily) and current smoker less than weekly.” We now have 13.8% of adults smoking daily, and a further 1.4% less than daily.

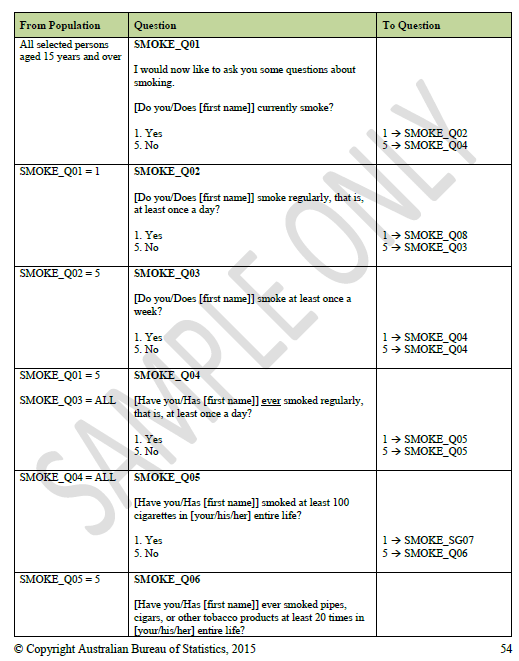

And very critically, unlike in the USA and the UK, Australian data on “smoking” explicitly include use of other combustible tobacco products (see questions establishing “smoking” below). This means that Australia’s 2017-2018 15.2% smoking prevalence includes exclusive cigarette smokers, all cigarette smokers who also smoke other combustible tobacco products and any smokers who exclusively smoke any of the non-cigarette combustible products (eg: cigars, cigarillos, pipes, waterpipes, bidis).

ATHRA repeatedly asserts that the US and the UK, both awash with ecigarettes, have both galloped ahead of Australia in reducing smoking. A tweet from November 9, 2018 (below) shows a graph they like to use.

US smoking prevalence: 14% … or as high as 17.3%?

ATHRA’s graph above shows the US National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) “18+ smoking rate” being 14% for 2017. NIHAS defines “Current cigarette smokers [as] respondents who reported having smoked ≥100 cigarettes during their lifetime and were smoking every day or some days at the time of interview.”

But in fact, 14% is the US prevalence for only cigarette smoking, not all smoking— see https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/SHS/tables.htm If we add all the other smoked tobacco products in widespread use in the USA (cigars, cigarillo, pipes, water pipes, hookahs, bidis) the prevalence of smokers who use any combusted tobacco product rises to 16.7% with an upper confidence internal boundary of 17.3% (see the table here). Quite a way above Australia’s 15.2% rate.

More recent US data for the first half of 2018 show “the percentage of adults aged 18 and over who were current cigarette smokers was 13.8% (95% confidence interval = 13.08%-14.53%) which was not significantly different from the 2017 estimate of 13.9%.” So far, ATHRA has not issued any public statements about the fall in cigarette smoking stagnating in the US despite some 3% of adults vaping, but these can’t be far off. Surely?

The year before (2016), also in the midst of untrammelled ecigarette promotions, the prevalence of current cigarette smoking among US adults was 15.5%, a slight but statistically nonsignificant rise from the 2015 figure of 15.1%.

Also, the 2016 NHIS US cigarette smoking prevalence estimate (15.1%) was a massive 24.5% lower than seen in the cigarette smoking prevalence figure (21%) for those aged 18+ in the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). With such different estimates, plainly, the real proportion is debatable.

A commentary in Addiction published in March 2017 commenting on another US survey noted “While it is possible that some proportion of non‐cigarette combustible tobacco use is concurrent with cigarette smoking, it is likely that overall combustible tobacco use prevalence for adults 18+ in the United States is higher than 15.2%, and somewhere in line or just below the 2013–14 National Adult Tobacco Survey (NATS) estimate that 18.4% of US adults aged 18+ were current users of any combustible tobacco product (defined by NATS as use every day or some days, with different thresholds of life‐time use by combustible tobacco product)”

UK

The UK government’s official smoking survey asks “do you smoke cigarettes at all nowadays? Please exclude electronic cigarettes”. In 2017, 15.1% of UK adults aged 18+ answered yes, but this figure also does not include people who smoke only non-cigarette combustible tobacco products such as cigars and pipe tobacco. So yes. 15.1% may be a cigarette paper below Australia’s 15.2% rate but it’s hardly a “man the lifeboats, the boat is sinking” difference that ATHRA and its spokespeople try to paint.

Latest adult prevalence data summary

- Australia: 15.2% (includes cigarette smokers plus all exclusive users of other combustible tobacco products)

- UK: 15.1% (cigarettes only: other exclusive combustible tobacco product users to be added)

- USA: 13.8% (cigarettes only: other exclusive combustible tobacco product users to be added)

And mostly down to ecigarettes?

ATHRA argue that the widespread use of ecigarettes is a major factor explaining the falls in smoking prevalence in the UK and the USA. The graph below from the Smoking in England project transposes the dramatically increased use of ecigarettes in quit attempts with the slow decline in adult smoking prevalence in England.

No one could look at this graph and point to any clear relationship between the two.

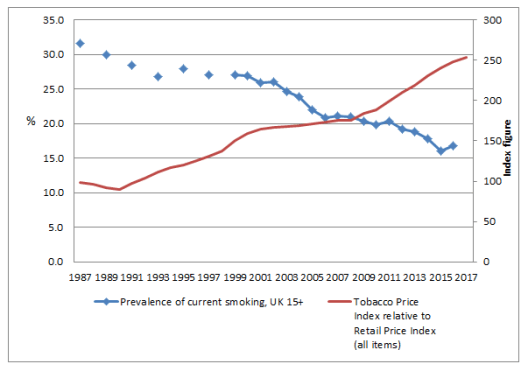

By contrast, the graph below shows the relationship between cigarette costliness and smoking prevalence in the UK. It is very clear that as the real price of tobacco rose (and hence costliness increased) that smoking prevalence fell, in an almost complete inverse relationship.

Source: Smoking prevalence and Tobacco affordability index

Huge prevention effect of Australian tobacco control

Colin Mendelsohn from ATHRA has been beating the same “the wheels have fallen off falling smoking prevalence” drum since 2017. I criticised his statements at length here in August 2017.

What’s missing in his almost total focus on what’s happening with smoking prevalence, is that while Australia’s current decline in smoking prevalence status compares favourably to the US and UK, our data on youth smoking prevention are quite stunning. Only 1.9% of 15-17 year old Australians smoked in 2017-2018, down from 2.7% in 2014-2015 and 3.8% in 2011-2012. This is a 50% fall in the 7 years 2011-2018, during which time Australia introduced plain packs and a series of annual 12.5% tax increases from 2013-2018.

The proportion of adult Australians who have never smoked was 52.6% in 2014-15 and rose to 55.7% in 2017-18. These figures are the tobacco industry’s on-going nightmare, presaging it as a sunset industry which will wither and starve from lack of “replacement” customers as its current users quit or die.

In my August 2017 critique I highlighted several reasons why Mendelsohn’s claim at the time that there had been an increase in the number of smokers in Australia needed careful circumspection. I wrote:

“Mendelsohn appears to have arrived at a figure of 21 000 extra smokers by multiplying the percentage of daily smokers listed for each year in Table 3 of the AIHW report, with an estimate of population numbers of Australians 18 years and over in June 2013 and 2016 released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics in June 2017. These population estimates were published some months after the AIHW would have undertaken the analysis of smoking prevalence for 2016 and some years after it released its estimate of prevalence in 2013.

The estimate ignores the complexity of how survey results are weighted by population composition. It also ignores the fact that the prevalence figure is only an estimate, with margins of error. The AIHW’s table of relative standard errors and margins of error indicates that the prevalence of daily smoking among people aged 18 years and over in 2016 was somewhere between 12.2% and 13.4%. This means that the number of smokers in 2016 could have been anywhere between 2 293 000 and 2 512 000. A similar range applies to the figure for 2013. The calculation of an extra 21 000 smokers between 2013-2016 is therefore essentially meaningless.

Moreover, the Australian Bureau of Statistics population figures show that between 2013 and 2016, Australia’s population aged 18 years and over grew by 864 340 people as a result of births, deaths and immigration. Many immigrants in this number would be from nations where smoking rates are high, particularly among men.

The elephant in the room? Massive growth in never smokers from smoking prevention.

Media attention has focused on smokers. But applying the same calculation Dr Mendelsohn has done for current smokers to people in the rest of the population, one would conclude that there are more than 870 000 extra non-smokers in Australia in 2016 than there were in 2013 — more than 80 times the number of extra current smokers (and more than 40 times the number of extra daily smokers) that he is so concerned about.”

ATHRA has egg on its face with its apparently naïve understanding of what smoking prevalence data for the three countries actually mean.

Professor Robert West (a leading figure in tobacco cessation research, editor-in-chief of Addiction and director of the large Smoking in England national study told the BBC in February 2016:

“[This widespread use of e-cigarettes] raises an interesting question for us: If they were this game changer, if they were going to be – have this massive effect on everyone switching to e-cigarettes and stopping smoking we might have expected to see a bigger effect than we have seen so far which has actually been relatively small” [my emphasis]

and

“We know that most people who use e-cigarettes are continuing to smoke and when you ask them they’ll tell you that they’re mostly doing that to try to cut down the amount they smoke. But we also know that if you look at how much they’re smoking it’s not really that much different from what they would have been doing if they weren’t using an e-cigarette. So I think as far as using an e-cigarette to reduce your harm while continuing to smoke is concerned there really isn’t good evidence that it has any benefit.” [my emphasis]

Esther Han at the Sydney Morning Herald reported earlier this year here about funding received by ATHRA from two companies involved in the vaping industry and here about their receipt of $8000 from an organisation that received funding tobacco companies.

Fortunately, governments in Australia have heeded the evidence reviews from the CSIRO, the Therapeutic Goods Administration and the NHMRC, and the advice from the overwhelming proportion of public health and medical organisations (table below) to take a precautionary approach about many of the over-hyped claims being made for ecigarettes and the vast areas of research where the evidence remains non-existent or very limited.

With multi-party support, Australia remains in the very front line of global tobacco control with commitments like plain packaging, high taxation, retail display bans and smoke free policies. Australia’s smoking prevalence would look a lot better if governments had not fallen asleep at the wheel in one critical areas- failing to run evidence-based national media campaigns since 2012.

ATHRA’s public statements need to be scrutinized very, very carefully.

Tailpiece

After it was recently announced that Philip Morris/Altria is planning to invest in cannabis, ATHRA’s Colin Mendelsohn tweeted on Dec 8 that it was “surely a good thing if they make money” from this move. With 20.8% of US high school kids now currently vaping (at least once in the past 30 days) compared to 3% of US adults, and the immense appeal of Juul involving its discreet properties (easily secreted, minimal clouding, memory stick lookalike), it is reasonable to ask what could possibly go wrong with PMI’s planned entry into the cannabis market. Vaping equipment is already being used to vape cannabis and other drugs. Philip Morris of course would be horrified if children were to vape dope before sitting down in the classroom. It would just never happen, right?

Excellent, Simon! Very appreciated!

Martina

LikeLike

Hi Simon,

Reading your observations reminded me of this quote i read recently in a review:

‘Opposition to e-cigarettes by those working in public health is often driven by implacable opposition to the tobacco industry, which is now making significant investments in vaping and other tobacco harm reduction products. Attacking the tobacco industry – and arguing that it has not changed – has become a mantra of some anti-smoking campaigners, who hate the idea of an industry they have been trained to vilify being let off the hook.

That has led to many US public health groups consistently stressing negative angles on vaping, and the FDA has chimed-in with its own regular highlighting of harmful chemicals and youth gateway effects’

Not suggesting this has any relevance to you of course. Just saying.

Best wishes, Colin

LikeLike

Colin,

No one needs to be ‘trained’ to vilify the tobacco industry. It’s not hard to figure out the need to do something about the vector of disease. If you aren’t chastened by Altria’s just-announced purchase of a 35% stake in Juul, I don’t know what it will take for you to see what’s at issue here. If you think e-cigarette companies are part of any solution to the crisis of tobacco product use, I have a bridge to sell you – Brooklyn, Golden Gate, Sydney Harbour, heck, I’ll throw in the Opera House. I’m not passive-aggressively ‘just saying’ it. Your position disregards the bulk of the evidence. The “negative angles” are numerous and all too real, not concoctions of the FDA and public health groups. The evidence on both the scientific and corporate fronts gives strong support for the precautionary principle.

LikeLike

Colin, seeing you said nothing about the focus of my blog (the accuracy of your repeated claims that Australian smoking rates have stagnated relative to the US & UK), I’m wondering whether you inadvertently posted this comment in the wrong place? I wrote this piece https://simonchapman6.wordpress.com/2018/10/22/is-big-tobacco-really-trying-to-get-out-of-tobacco/ looking at the proposition that the tobacco industry is really trying to get smokers to quit smoking Feel free to give us your wisdom over on that link.

I’d be interested to learn of a single example of any tobacco company desisting from its efforts to wreck effective tobacco control policies, stop its tobacco promotions etc while blathering about their earnest hopes that people should stop smoking. Anyone who believes that the PM fully-funded Foundation for a Smokefree World is a credible exercise in reducing smoking would probably believe that a Casanova Foundation was a credible body to promote the preservation of women’s chastity.

LikeLike

Playing with a double edge sword here. If an increase in vaping hasn’t caused an increase in tobacco consumption, then you rule out any justification to deny the population access to vaping products.

As Dr. Peter Hayek said, it’s the only thing that matters; https://i.imgur.com/bRFnI6Y.jpg

That said, I wouldn’t trust any data on the prevalence of vaping in any study to date that have relied on self-reports.

I know several exclusive tobacco smokers who have purchased a vape system, and when asked if they vape, will answer “yes” – simply on the basis that they own a vape system. When asked if they have used their vape system in the past month, they will answer “yes”, in order to please the person asking.

In reality, these people don’t vape. Their vape system sits at the bottom of their kitchen draw uncharged, and their e-liquid sits above their fridge expiring long past it’s due date. From observation of dozens of smokers, long term dual use appears to be non-existent. Smokers will either quit smoking and become exclusive vapers, or continue smoking while their purchased vape system collects dust.

We don’t know the true prevalence of vaping because interviewers have never asked the right questions to properly determine if a person really vapes. A better approach is needed to determine how many people are really vaping. I think the most accurate information will be to look at their spending habits. People who don’t vape, don’t spend money on e-liquid. Another approach would be to ask the person details about their vape – People who don’t vape tend to know very little about their device, sometimes these people can be caught out simply by asking them what make and model their device is. A person who vapes and regularly purchases new atomizer coils for device can answer these questions without hesitation.

LikeLike

Ben, I’m certain you are correct that there are many unused sets of vaping gear that have been bought and now sitting in drawers. The same observation can be made about purchases of clothing, books, fad gadgets, yo-yos, etc etc. While I don’t dispute the authenticity of your informants’ claims that they want to “please” those conducting surveys by assuming that interviewers on surveys all somehow want a particular answer to be given (yes, I vape), if you think about it, this is a very strange assumption. Why would those working to collect data for the Australian Bureau of Statistics be expected to have a preferred answer on vaping, any more than they would have a preferred answer on any other question being asked in a national health survey.

Precautionary government and health agency policy on vaping is not based just on concerns about whether it might increase the likelihood of smoking (I’ve written about that here https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/bitstream/2123/17579/2/Etter%20response.pdf )

Other concerns are whether it might hold many people in smoking (dual use) who might have otherwise quit and whether it may cause serious health problems down teh track. The health problems of smoking did not become apparent for decades after the massive upswing in smoking that followed the mechanisation of cigarette production early last century (with this causing the price to fall dramatically). Almost every week, very concerning new studies are being published about respiratory and other problems . You’re unlikely to see those on pro-vape websites & chatrooms

LikeLike

My concern is that there have been mostly false positives recorded concerning Dual-Use. It’s not the matter of those working to collect data for the Australian Bureau of Statistics to expect a preferred answer on vaping, but the perception of the person being interviewed.

Smoking is extremely stigmatized in our society, and when a person who smokes is asked about their smoking behaviour, there will always be a high chance of that person downplaying how much they smoke, and up-playing their use less dangerous alternatives. A more objective approach to examining vaping behaviour is required, and I think this will revolve mainly around qualifying questions designed to exclude those who are up-playing their vaping behavior.

Questions regarding how well the person knows their vaping product are crucial questions to ask in order to determine if they really do use their device. Example questions would include;

“What is the make and model of your atomizer tank?”

“What type of coil do you use?”

“What is your ejuice Vegetable-Glycerine/Propylene-Glycol ratio?”

A person would not be able to purchase ejuice refills and replacement atomizer coils without this basic information. Inability to easily convey these basic specifications of their vape-system would strongly suggest that they do not use their device.

I agree that it is vitally important that health concerns related to exclusive vaping should be monitored closely over the next few decades. There are extensive discussions on vape-related online forums that delve into this subject, and many vapers, as well vape product manufacturers pay close attention.

For example, several companies have developed temperature controlled devices which regulate the power output of a device to ensure that the temperature of the atomiser does not exceed a certain threshold, hence limiting burning and the production of harmful compounds. I wont link to any specific product, but these devices can be found by google searching “temperature controlled mod”.

In addition, several food flavoring companies that noticed an increase in sales over the years due to vape-related sales, have paid attention the studies by Farsalinos et al. on diketone flavourings such as Daicetyl and Acetoin, and now sell versions of their flavors that are free of diketones. Notable examples are Capella and The Flavor Apprentice;

https://www.capellaflavors.com/a-p-status/

https://shop.perfumersapprentice.com/t-FlavorWorkshopCustard.aspx

I believe there is a consensus among the vaping communities that ejuices labels should include ingredients listings to allow consumers to avoid ejuices containing diketones. Personally, I would like flavors containing diketones banned.

It should also be pointed out that tobacco companies nor their vape-product subsidaries have ever partaken in any of this development to improve the safety of vaping. It has mostly been a grass-roots effort.

LikeLike

Hi Ben, I think your ” tobacco companies nor their vape-product subsidaries have ever partaken in any of this development to improve the safety of vaping. It has mostly been a grass-roots effort.” would greatly amuse the Big Tobacco companies investing massively in HR products. As you must know, Philip Morris has bought a 35% share in Juul, and NJoy which sells refills with nicotine salts is hardly “grass roots” https://njoy.com/pre-filled-tanks/. So

I note your comments on a limited number of flavourings but you should note the statement of FEMA “None of the primary safety assessment programs for flavors, including the GRAS program sponsored by the Flavor and Extract Manufacturers Association of the United States (FEMA), evaluate flavor ingredients for use in products other than human food. FEMA GRAS status for the uses of a flavor ingredient in food does not provide regulatory authority to use the flavor ingredient in e-cigarettes in the U.S.” https://www.femaflavor.org/member-update/safety-assessment-and-regulatory-authority-use-flavors-focus-e-cigarettes

In an ideal world, questions on tobacco use would all be biochemically validated and the sort of questions you suggest asked. But the bar that would set is so high (expense wise and in terms of what it would do to savage response rates) that people who are vastly experienced in these matters at the ABS plainly do not consider them realistic.

There is a big literature on the validity of surveys of smoking prevalence. In general it shows most under-reporting occurs when respondents know that those questioning are not independent or when there is very high stigma involved (ie pregnant women).

LikeLike