In my first weeks working at the University of Sydney in the late 1970s, I received a tip-off that a lunchtime talk in the School of Economics would be led by a student who was a Rothmans employee. I went along to a room where about 20 listened to a highly detailed and occasionally furtive talk about how Rothmans gathered its intelligence about what impacted its cigarette sales. The audience were all economics wonks interested in data processing. But I had my then innocent eyes opened to something elementary I’d never forget.

He explained something obvious, if you thought about it. The company had day-by-day, suburb-by-suburb, shop-by-shop and brand variant by brand variant sales data. This was routinely gathered from its delivery van drivers at the end of each day after their stock drop offs. Their sales analysts could map these data against any variable of interest: their prices and those of their competitors, against advertising launches and campaign reach , seasonality and to assess the impact any further bad news reporting on tobacco and disease, or any new policy or campaign the government introduced designed to reduce smoking.

The delivery drivers and a small army of sales workers would also gather qualitative information from shop staff about what customers were saying about anything relevant to smoking. In two papers, my research group later looked at how this was used here and here.

Unsurprisingly, the information collected by on-the-ground staff is used to shape and fine tune company efforts to maximise sales and profits. Compared to the delayed and state or nationally aggregated information available to those in public health via large cross-sectional surveys done every few years, the industry’s intelligence about changes was Exocet precise. Today with instantaneous sales data recording, business intelligence is lightning fast. Price discounting remains the main strategy left to an industry that cannot advertise, promote, place its deadly products in highly market-researched packaging or even display it in shops.

The memory of the Rothmans guy’s presentation came back to me when I read an opinion piece this week in the Guardian coauthored by Ed Jegasothy, from the School of Public Health at Sydney University and Francis Markam from the ANU. Their drift was that Australia has lost its way in tobacco control, despite – they acknowledged — tobacco being “a vitally important public health issue” and smoking rates having “declined remarkably”. They declared that the “growth of the black market fundamentally undermines the health aims of the tobacco excise”.

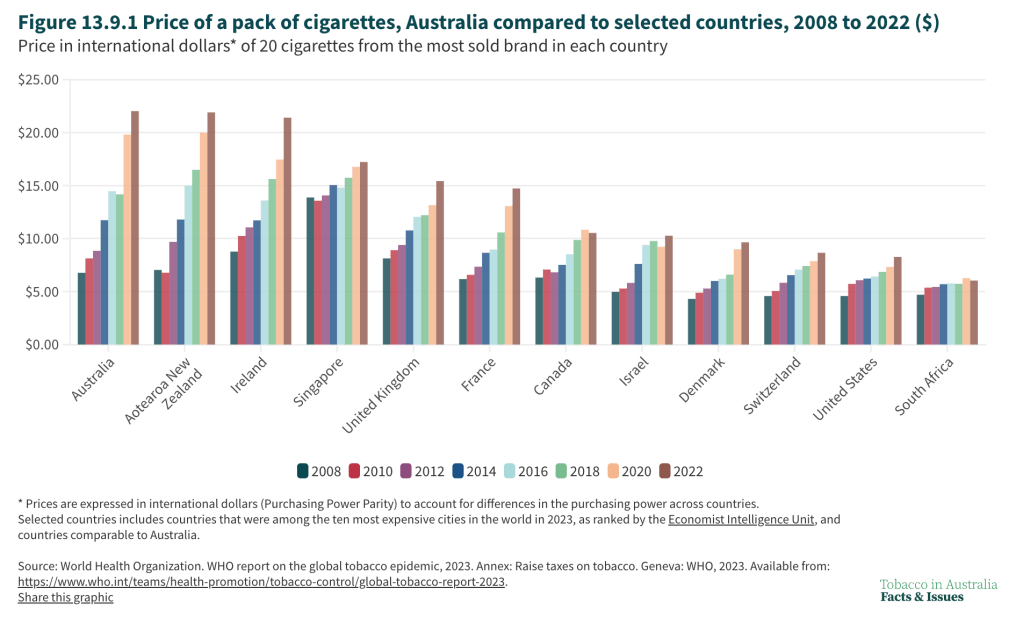

So are we all getting confused here? Or perhaps it’s the authors who are? If smoking rates have declined remarkably (yes, true see their graph and see here for extra detail on just how much), how has the rise of black market retailing undermined the “health aims” of the tobacco excise when presumably this means lowering smoking and after a lagged period, the diseases it causes?

The major rise of illegal cigarette retailing has certainly eroded excise receipts, but when we survey to measure smoking prevalence, we count smokers regardless of how they buy their cigarettes – excise paid and excise avoided are both counted. Both licit and illicit tobacco kill smokers.

Last year I began seeing Jegasothy quoted in news media on the issue of tobacco tax and smoking prevalence, particularly in low socioeconomic people. Curious, I looked up the authors’ track records on tobacco here and here. Between them they have just one published letter to a peer reviewed journal. [update 20 Jul 2025: they have since published this so far uncited paper on 24 March 2025. To date it is the only paper to have (self-cited) their earlier published letter from July 2024]

This was a critique of a paper on the impact of Australia’s tobacco tax on smoking prevalence. The authors of that original paper responded to the critique with an iron fist in a polite velvet glove writing diplomatically that serious criticism here “should be based on a deep understanding of the tobacco control landscape over this time period” and pointing out why the time period their original study had examined was most appropriate.

The simplistic scream test

Early in their Guardian piece, Jegasothy and Markam disparage the notion that what the tobacco industry protests most about is reasonably seen as a litmus “scream test” for policies that it cares most about. Linking to a recent Four Corners program where I used the expression, they call this “simplistic reasoning” because tobacco manufacturing and retailing price components often quietly rise under the air-cover of heinous, cruel tax rises that grab the headlines. So as long as Big Tobacco is still profitable despite tax rises, they couldn’t care less about these rises. Is that their interesting reasoning?

True, the industry has a history of raising its margins and profiting even further in the shadows of tax increases, but notwithstanding, here are a few historic examples of the industry screaming about tax. The tobacco company Philip Morris (Australia) in 1983 said:

… The most certain way to reduce consumption is through price.

Then again in 1985:

… Of all the concerns, there is one – taxation – which alarms us the most. While marketing restrictions and public and passive smoking do depress volume, in our experience taxation depresses it much more severely. Our concern for taxation is, therefore, central to our thinking about smoking and health. It has historically been the area to which we have devoted most resources and for the foreseeable future, I think things will stay that way almost everywhere.

And 1993:

… A high cigarette price, more than any other cigarette attribute, has the most dramatic impact on the share of the quitting population.

In 2011, British American Tobacco’s boss in Australia, David Crow, publicly acknowledged the impact of tobacco tax, telling a Senate committee:

We saw that last year very effectively with the increase in excise. There was a 25% increase in the excise and we saw the volumes go down by about 10.2%; there was about a 10.2% reduction in the industry last year in Australia. (see here at p xviii)

So if these (and many more like them) do not indicate virulent industry concern about tobacco tax, why has it carried on screaming about tax in the same way for at least 42 years?

How low would tobacco tax need to go to make the black market disappear in Australia?

They write that “government officials remain inflexible, rejecting even temporary pauses in tax hikes”, let alone countenancing the profanity of significant falls in tobacco excise duty.

But those who blithely call for tobacco tax pauses or cuts never name the size of the cuts that would make illegal, duty-not-paid cigarettes less attractive to low-income smokers. Why be so shy? Let me assist here by repeating what I wrote in my last blog.

It’s easy to call for “lower” tobacco tax, but how much lower would it need to be to see budget-conscious smokers switch back to buying taxed cigarettes? A common price for the most popular illegal brand of cigarettes in Australia is $15. The current excise rate on cigarettes in Australia is $1.40313 per stick. So the tax alone on a pack of 20 cigarettes is now $28.06.

A common retail price for popular brands of legal duty paid cigarettes is around $40, with the extra component costs (after tax is deducted) being those going to cigarette manufacturers and retailers. Given that tobacco manufacturing and retailing interests are not talking at all about radically dropping their margins to compete with $15 illegal pack prices, are the “cut the excise” voices then suggesting that the government should therefore “take one for the convenience stores” and give up perhaps all of its tobacco excise ($40-$28 = $12), a price that would certainly go near to blowing illegal retail trade out of the water?

We don’t know how low illegal cigarette retail pricing could fall even further to still remain very profitable to those running it. But by now, simplistic calls to “cut excise” lead us very quickly into this truly absurd territory, when the obvious solution is instead for governments to crack down hard on the illegal retailers, importers and wholesalers. Small cuts would make no significant difference to the large gap between legal and illegal cigarettes. Only massive or even entire scrapping of tobacco excise would bridge that gap. And pigs might fly in that space.

Where incomes are unequal, pricing of every commodity is regressive

In May 2023 Jegasothy published a blog The tobacco tax hike is not a public health measure: it’s a regressive tax grab. where he concluded for tobacco tax rises “The policy has not been successful in meeting the bar of being effective, equitable, or ethical.”

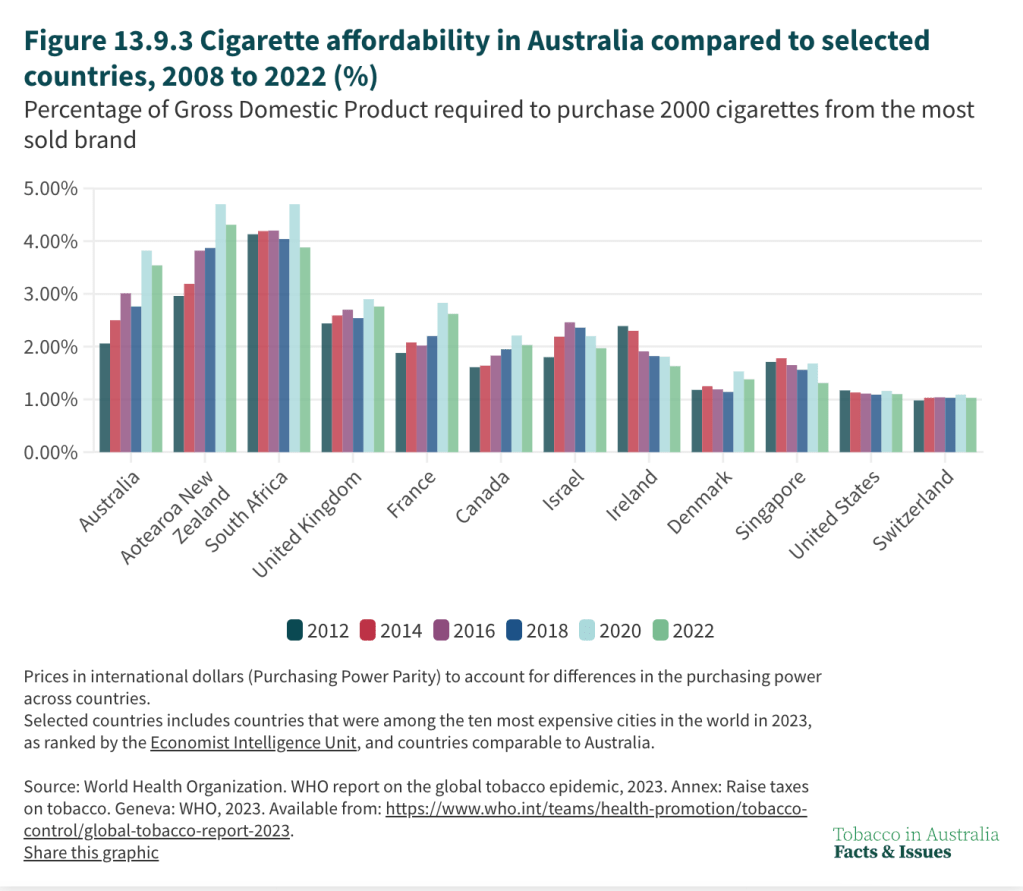

When there is income inequality in a society (which is and has always been the case in every nation) then there is inequity in the ability of people with different means to pay for any and every commodity or service, from basic necessities to luxury goods. Cigarettes are no different.

Lowering the price of tobacco would be a disincentive to quitting and reducing the number of cigarettes smoked per day by continuing smokers (this has fallen by 40% from 20 in 2001 to 12 in 2019). It would erode the severe disincentive to take up smoking by highly price-sensitive kids and it would make Australia a pariah in global public health by making it an easier decision to smoke.

Oh, the irony … cheap illicit cigarettes “help the poor” right now

The huge irony in Jegasothy and Markham’s piece of course is that because the most price-sensitive smokers are heavily attracted to cheap duty-not-paid cigarettes, it might be argued that the black market is right now a huge welfare gift to low-income smokers. If every time a pack-a-day smoker buys a $15 pack of black market cigarettes, they save $25 on what they would have paid to buy a popular taxed brand. That’s an annual saving of $9125. So why aren’t they out there urging low income smokers to count their luck and providing lists of illegally trading shops to support them in saving money?

Here of course, they’d be thoroughly wedged by the knowledge that smoking kills up to two in three long time users. Any public health researcher urging that poor smokers be given every encouragement to keep smoking by lowering the price they pay would be recommending a truly perverse way of ‘helping’ disadvantaged people.

Not just tax driving smoking down

In their Guardian piece. Jegasothy and Markham hint that other tobacco control measures may even work better than excise policy.

“Smoking rates have declined remarkably – but at similar rates during periods with and without significant tax increases. This suggests minimal impact from the tax hikes themselves.”

They write that tobacco tax policy is “central” to tobacco control policy and that “policy discussions have been “fixated on tax as a silver bullet” and note that “smoking rates fell during periods of price stability indicates that shifting social attitudes and cultural norms around tobacco use, as well as policies such as smoke-free areas, are playing significant roles in reducing smoking prevalence.”

First, note here that there have been no periods of price stability across the years they consider. Prices have risen over the entire period. And in any case, it’s not just any acute, immediate effect of the increases that needs to be considered. Costliness/affordability exerts an impact even during periods between that dates when increases happen.

All this evinces large scale ignorance of the core guiding principle of tobacco control which has never been only about tobacco tax. Since the 1970s, comprehensive policies and programs in reducing smoking through both preventive and cessation impacts have been the tobacco control policy template. Anyone who has worked in tobacco control and read its vast research literature knows understands this as ABC level awareness.

Far from being fixated on just tobacco tax, those working in tobacco control in Australia from the 1970s have fought (and won) a multitude of policy battles that in total have greatly increased consumer agency and profoundly changed social norms about smoking. Here are some highlights:

- Four generations of pack health warnings starting in 1973, all resisted tooth and nail by the industry, with a fifth due for introduction in July this year

- Bans introduced between 1973 and ‘76 of advertising of cigarettes on TV and radio, later extended to cinemas, and in print media in 1989 and the internet in 2010

- Total bans on advertising and promotion on billboards, outside shops, on public transport vehicles and shelters and throughout all sponsorship of sport and the arts

- Complete indoor workplace smoking bans, including on all public transport, and in all restaurants, clubs, bars and pubs. Workplace bans reduce number of cigarettes smoked over 24 hours and were responsible for about 22% of the total decline in tobacco consumption in Australia between 1988-1995 when they were being introduced

- Mandatory smoke-free zones in shopping malls, children’s playgrounds and between the flags on beaches

- Unique among all general retail products, retail display bans (all stock kept out-of-sight)

- Introduction of world-leading and emulated mass reach public education programs in every state and territory and nationally

- Globally unique plain tobacco packaging commenced in Australian in 2012, starting a global domino effect that now sees 24 nations having implemented or legislated for their introduction, with more on the way. The industry invested massively to stop this, but always lost

- end of all tobacco growing in Australia (this let the air out of the industry’s tyres to lobby via growers in the few electorates where tobacco was once grown)

- end of all tobacco manufacturing (BAT and Philip Morris products are all now imported). This benefits tobacco control because there’s now negligible local industry employment and all profits are repatriated, a disbenefit to the balance of trade and therefore an incentive for governments to reduce smoking further)

- world’s highest retail price of tobacco led by tax policy and the industry using tax rises as air cover to raise their own margins

- ban on personal importation of cigarettes by mail

- Import duty free limit of 25 cigarettes in an open pack

- An end to misleading product names and additives that make cigarettes more palatable to children (due for introduction from July 2025)

- The Liberal, Labor and Greens parties all refuse tobacco industry donations, unique among all industries

- No university allows staff to accept tobacco industry grants or students to take scholarships

- Only far right fringe of politics would ever be seen in a photo opportunity with tobacco or vaping interests.

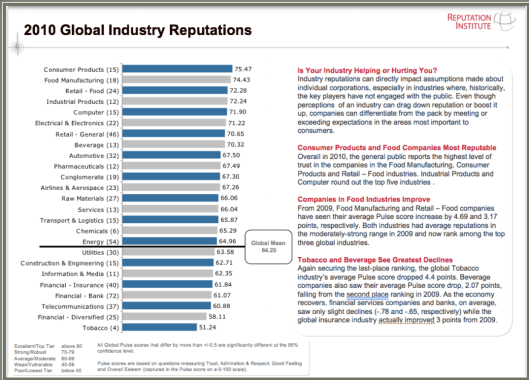

- Big Tobacco has long ranked (way) last as the industry with the lowest reputation (see chart below)

- Widespread denormalization of smoking

- The industry understands that all the above make it an unattractive employment choice which creates staff quality problems

Like Jegasothy now, I worked in the University of Sydney’s School of Public Health for several lengthy periods from 1977. I helped write and teach units of study in the first year in the first Masters of Public Health in the southern hemisphere and spent 17 years editing the BMJ’s specialist Tobacco Control journal from its 1992 launch. I’ve never met Ed and am unaware of any contribution he has made to tobacco control other than through his efforts to critique tobacco tax.

Criticism is a sacred duty of scholarship, but so is collegiality and constructiveness. Regardless of how much of a role taxes have played in reducing smoking in Australia, cutting them now would undoubtedly increase smoking, particularly so among young people and the most disadvantaged Australians. This is why every player with financial skin in the game is piling on to attack excise taxes.

Informed specific investigation of ways of actually reducing illicit trade in tobacco are the global focus of a huge amount of scholarship and collaborative work. It is an immensely sticky problem. No party with any standing, track record or credibility calls for the same response that those invested in having as many as possible smoking support tax cuts.

Australia has pioneered the regulation and sale of a large and diverse list of both useful and harmful consumer goods. Firearms, prescription medicines, asbestos, unleaded petrol, vehicle and consumer safety standards are several examples. We have an enviable track record and matching outstanding global ranking on health vital statistics. No nation has ever eliminated illegal tobacco, but many are now watching how current efforts will progress.