Tags

Australia’s epidemic of illicit (untaxed) cheap cigarette shops is entering a new phase as Australian Border Force reports record seizures and three states (South Australia, Queensland and New South Wales) have taken off the kid gloves and are now hammering illegal tobacco retailers.

Australian Border force data show “From 1 July 2024 to 30 June 2025, the ABF made 23,097 illicit tobacco detections, seizing 2.53 billion cigarette sticks and 435.46 tonnes of loose-leaf tobacco. This equates to a total of over 2,091 tonnes of illicit tobacco products seized and prevented an estimated $4.36 billion in duty evaded across the financial year.” In the first quarter of the 2025/2026 financial year, a further “586 million cigarettes and over 3 million vapes have already been seized at the Australian border in the first quarter of this financial year (1 July – 30 September)”.

Queensland has recently introduced fines of up to $161,300 or one year jail for a commercial landlord who knowingly allows a tenant to sell illegal cigarettes and vapes. Its store closure powers are now 3 months, up from a mere 72 hours, once commonly referred to as “the tobacconists’ long weekend”. The Health and Ambulance Services Minister Tim Nicholls describes the new laws as “an absolute game changer“.

South Australia has now closed 100 shops for 28 days, with two closed for much longer with another eight before the courts facing long term closure and massive fines; seized 41 million cigarettes (2.05 million packs); and 140,000 vapes.

NSW Health began getting serious when legislation enabling on the spot 90 day closures, stock seizures, landlord fines and serious maximum on-the-spot fines ($1.54m) came into effect from the first week in November. The Department updates its register of busts each Friday, with the current list now at 40 closures.

In early December raids on homes and storage facilities saw arrests and seizures of 10 tonnes of illegal tobacco.

Western Australia and Victoria which have historically been on the national podium for their early adoption of most tobacco control laws and regulations but look certain to get the booby prize on this issue, both still playing catch-up with other states .

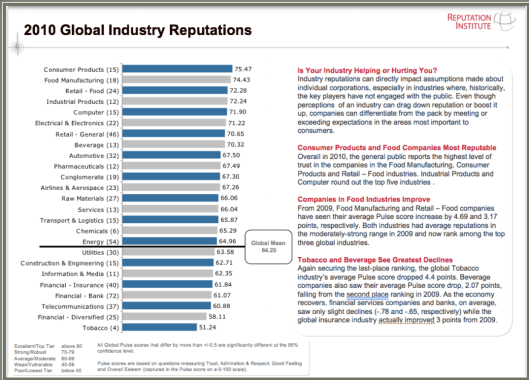

For as long as governments have taxed tobacco, tobacco companies have lobbied for the taxes to be frozen or reduced. For over 40 years they have had day-by-day, shop-by-shop, brand-by brand data on the sales impact of every variable know to reduce or increase cigarette sales. Significantly here, tax increases have always been in the industry’s crosshairs because they depress sales.

Sweet spot tax fantasies

It’s been standard for several years now for those in lockstep with Big Tobacco’s calls for lowering tobacco tax to call for a halt to rises and to make allusions to tobacco excise tax actually falling. Deakin University criminologist James Martin has been in the forefront of these calls for Australia’s tobacco tax to be lowered but until quite recently had been too shy to give us all his expert figure on a new “sweet spot” for a tax reduction. This would be the point where many smokers would abandon buying cheap illicits and go back to paying for legal taxed cigarettes.

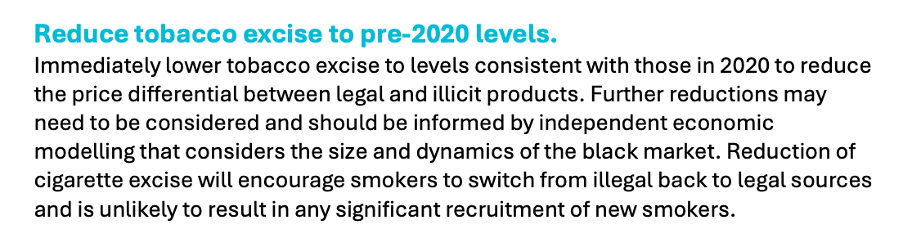

Today, if you buy a carton illegal cigarettes, you can get them for as low as $7 a pack of 20. A common range for a single pack is $10-$15. Martin and Alex Wodak dodged naming a tax rate in July 2025 in a Crikey piece when vaguely urging “reducing tobacco excise to undercut the illicit trade”. Something called “Harm Reduction Australia” published an unsigned Tobacco Harm Reduction Policy Brief , presumably covered with the fingerprints of its tobacco harm reduction advisors, Wodak and Martin. They suggested that the tax be reduced to the level it was in 2020. In this August 2025 blog, I did the maths, and generously took the hypothetical cuts even further back to 2019 tax levels to see how things tasted.

If this occurred today, the retail price of a reduced tax pack would fall to some $22, still $7 or 47% more than a pack of $15 illegals or $15 more than the $7 a pack when buying by the carton price.

So on what planet would anyone be living on who seriously thought such a tax reduction would see droves of smokers rush back to the newly reduced tax legal cigarettes?

Eliminate tobacco tax … to get more smokers buying taxed tobacco!

This ludicrous penny may well have finally dropped for Martin when in November he was publicly quoted in the Singapore Straits Times that “taxes would need to be significantly lowered and even eliminated to discourage criminals from operating a black market.” [my emphasis]. Eliminated. Now how would this work?

Let’s walk through his brilliance.

So … the government has a problem that it’s losing lots of tax revenue because many smokers are buying illegal untaxed cigarettes. To fix this, Martin suggests that the government should consider dropping all tobacco tax. If it did this, there would of course be no tobacco tax to collect, but, hey, these now (legal) untaxed cigarettes would be competitive with (illegal) untaxed cigarettes and the black market would be “discouraged”. All following this?

But wait… with the newly tax-free legal cigarettes, where would the government get the extra river of gold of tobacco tax revenue from that it desperately needs, since it would have just eliminated it all? Whoops!

Enter the Davidson

The latest player to step forward into this mess is Professor Sinclair Davidson from Victoria’s RMIT. Davidson, an adjunct ‘fellow’ at regulation-scything Institute of Public Affairs has been an anti tobacco control warrior for sometime via his now defunct Catallaxy Files blog and his four time participation in Big Tobacco’s annual invitation-only global shindig, the Global Tobacco and Nicotine Forum.

In a paper for the Centre for Independent Studies, Davidson is also shy of telling us what his tobacco tax cut/illegal tobacco ending magic number is. All he’s willing to say is that it would be “stabilised within an economically defensible range”. And that would be?

Google Scholar shows Davidson has had 320 publications since 1991, 134 (42%) of which are uncited. Six of these are about tobacco, which have attracted all of 26 cites. That’s his form in all this. Still, a 42% never-cited rate is a lot better than the 82% rate reported across the humanities.

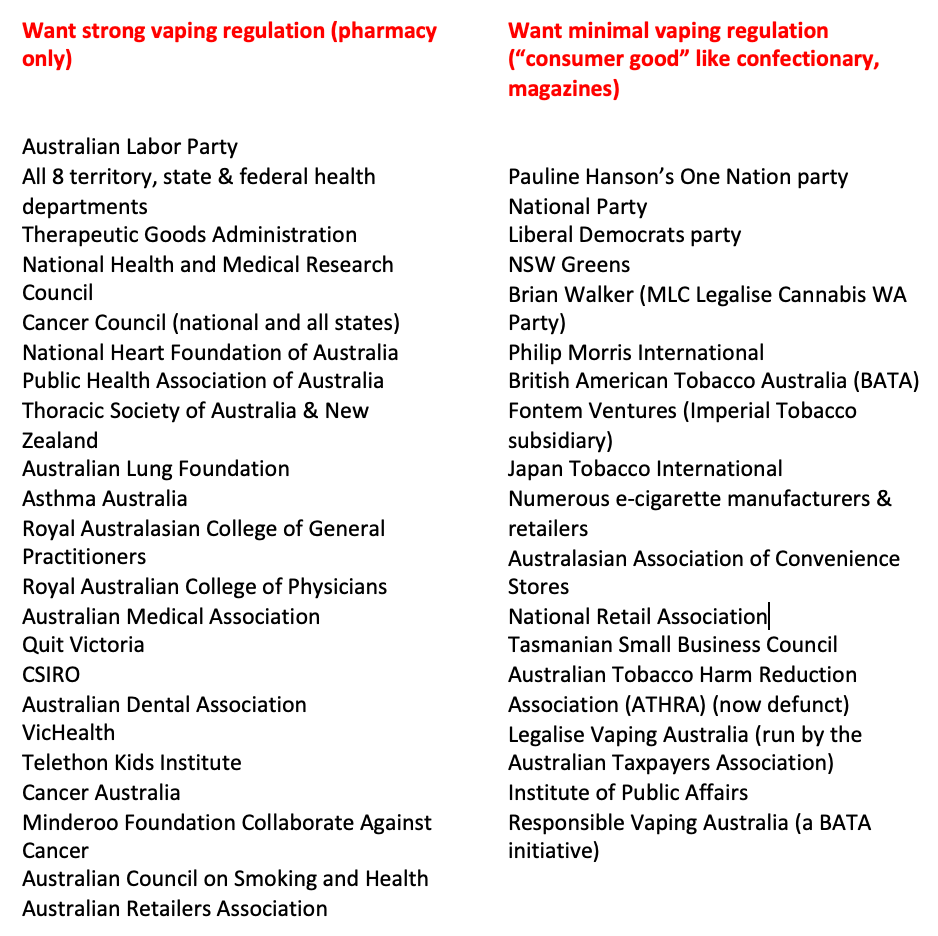

Those lobbying hard to get governments to do something sensible to wreck Australia’s illegal tobacco and vapes market are in an unlikley choir that has never sung from the same hymn sheet before. It includes Treasury, the convenience store, tobacco and vaping industries, and public health. All are very keen to see illicit tobacco trade fall dramatically. Treasury wants tobacco tax to grow, and the three industries want their tobacco sales revenue streams back. Public health and government want smoking to fall, and non-smokers (especially kids) to not buy vapes or tobacco, as they increasingly are failing to do.

Wastewater nicotine analysis: total nicotine is falling, not rising

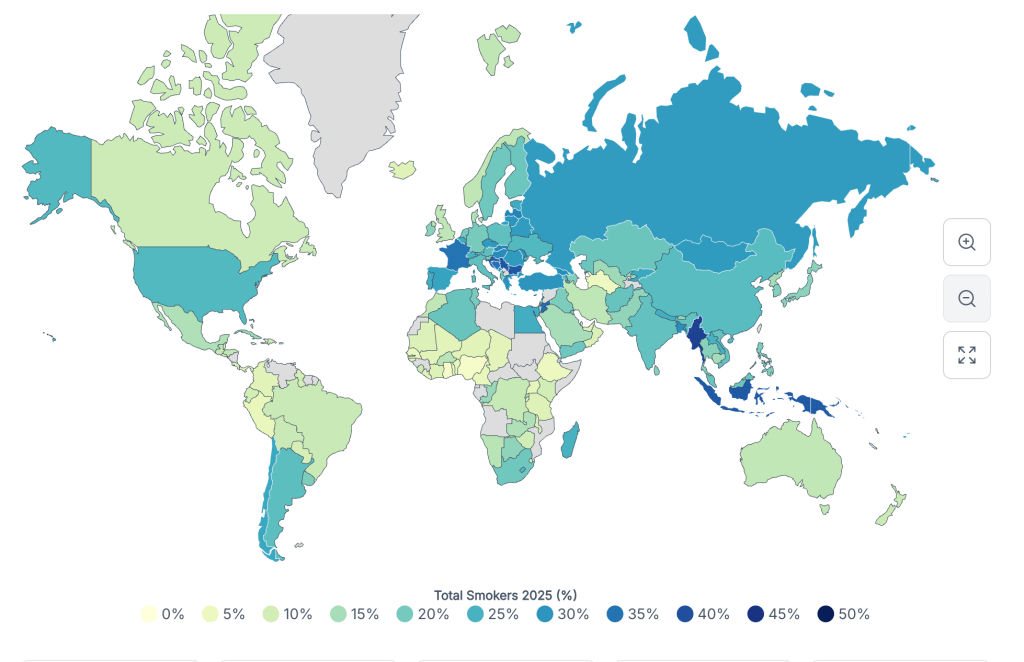

Here, wastewater nicotine analysis offers a potential lever for the industry interests to pull in its lobbying for tax reduction. We have all seen illegal tobacco shops openly trading, and some think this must mean that more people are smoking to make this trade viable. But is it actually true that cheap illegal cigarettes are causing more people to take up smoking and less to quit? Or is it just moving lots of current smokers from legal sales outlets to much cheaper illegal ones?

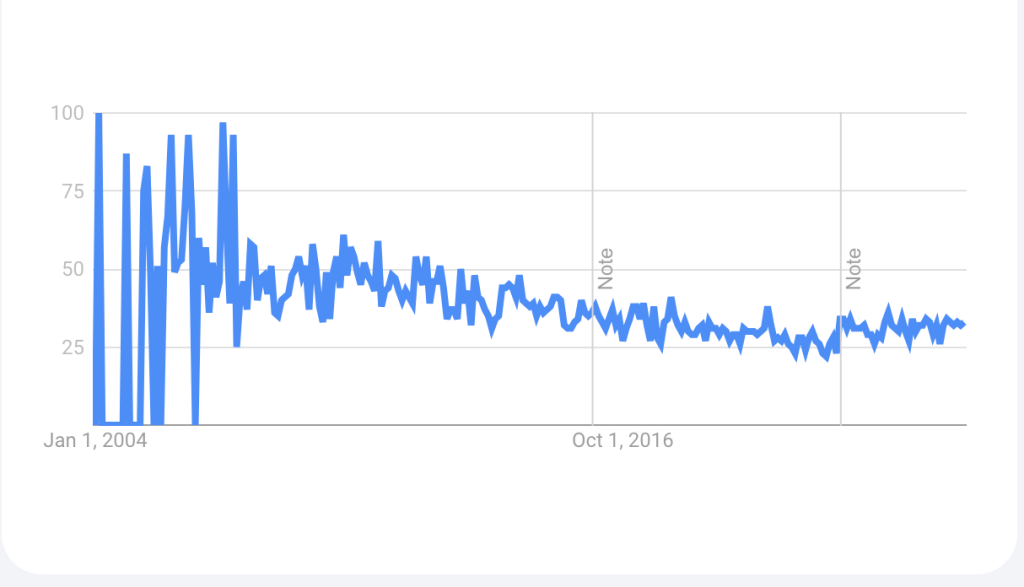

Here, Davidson quotes from the National Wastewater Drug Monitoring Program’s (NWDMP) latest report for 2023-24 .They have been testing since 2016-17, publishing data on nicotine found in wastewater (sewage) in testing sites serving 57% of the Australian population (14.5m) with both regional and capital city sampling.

The summary below from its latest report shows that between April and August 2024, population weighted nicotine consumption fell in both regional and capital city Australia. In fact this fall has been going on since August 2023: page 16 of the report states that while illegal tobacco and vape retailing was booming “for nicotine, average consumption [across Australia] decreased between August 2023 and August 2024” Although page 87 notes that “average capital city nicotine consumption then increased from August to October 2024”.

Contrast those words with Davidson’s at p6 of his report “Wastewater analysis reinforces this picture: between August 2023 and August 2024, aggregate consumption of nicotine rose to above long-term averages”. The NWDMP reports on “average consumption decreased” (ie population weighted) while Davidson says “aggregate consumption … rose” (ie total consumption unweighted for population growth).

Sorting different sources of nicotine

The NWDMP’s testing to estimate consumption of nicotine is done by measuring two nicotine metabolites, cotinine and hydroxycotinine. Their report notes on page 32 that this method “cannot distinguish between nicotine from tobacco, e-cigarettes, or nicotine replacement therapies such as patches and gums” and that “consumption of nicotine has increased over the life of the Program” (p59)

This is hardly surprising. Vaping in Australia rose substantially between 2019-2023 and in 2022-23, 233,544 PBS prescriptions were issued for nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), some 43% of the estimated NRT market (a majority of which is over-the- counter sales in pharmacies and supermarkets). So together with nicotine from vapes, this NRT sourced nicotine represents a river of excreted nicotine in the sum of total nicotine in Australian sewage systems, a point acknowledged by Davidson.

Emerging science points to possibilities of testing wastewater to get separate estimates for total nicotine (cigarettes, vapes and NRT combined) including that only from cigarette use. Anabasine and anatabine are minor alkaloids found in tobacco but are absent in NRT. However anabasine is present not just in cigarettes but also in e-liquids and aerosols. So challenges remain to test for estimates of only tobacco use (leaving out NRT and vaping nicotine exposure).

This is an area of science very much in its infancy, with the take-home message being that we all need to remain sceptically alert to crude claims that “wastewater” analysis is showing changes one way or the other in tobacco smoking.

Those in Australia who have collectively decades of experience in monitoring and interpreting different data sets on tobacco use, repeatedly emphasise that longer term data from multiple sources including survey data are essential in getting a true picture of trends. Prof Coral Gartner from the University of Queensland said that “All data, including that from wastewater, has limitations and errors, including seasonal effects. What may look like an increase in one data collection can become just ‘noise’ when further data points are added.”

If you search “wastewater and nicotine” for Australia, stand by for reports on the latest NWDMP data that variously describe nicotine as being up or down. Those catastrophising the possibility that smoking will be certain to rise in the presence of cheap illegal cigarettes can take nothing definitive from the latest wastewater statistics. But with those who collect and interpret it saying that total nicotine is down across the country, those saying it is up need to explain themselves.